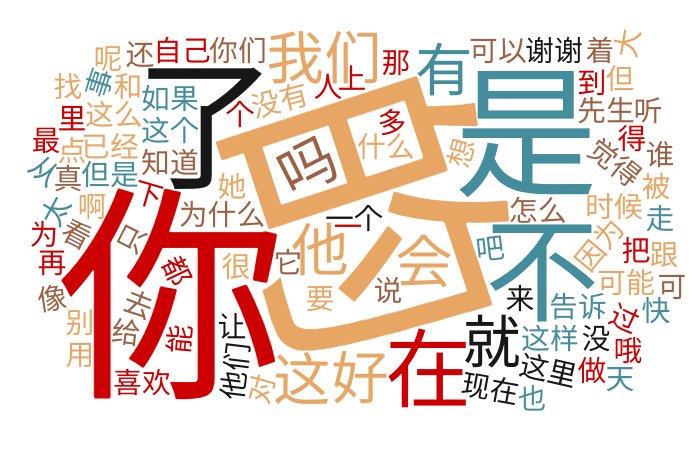

How much Chinese you learn depends on three things: how you study (method), how much you study (time) and what you study (content). If you want to learn as much as possible, you need to maximise all three. When it comes to Chinese vocabulary, many underestimate the importance of what you study. Memorising hundreds of vocabulary items is great, but it will only have a great effect on your ability to communicate if you learn the most common Chinese words, characters and words!

So, what should you learn? This is easy to answer in the abstract: you should study whatever is the most useful to you, based on your goals for learning Chinese. In practice, this is harder to answer, though, but fortunately, we can use frequency as a proxy for usefulness. This is based on the assumption that something that occurs often in the language ought to be learnt before something that is less frequent, simply because you’re likely to both use and encounter it more.

To read more about the three factors (method, time and content), check out this article: Three factors that decide how much Chinese you learn.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Please note that the most common Chinese words are not necessarily the most useful ones. Other ways of accessing lists of useful characters and words include vocabulary lists from textbooks, standardised proficiency tests and more. For a discussion about that, please check the article below.

Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them

In this article, I will only talk about frequency.

Frequency resources for learning and teaching the most common Chinese words, characters and components

The problem is that students, and sometimes teachers, have a simplistic view of what frequency lists are and what they can or should be used for. It’s easy to grab a list off the internet and use it as an absolute reference, believing it to show the most common Chinese words, characters and components.

It probably does, but it’s important to remember that all frequency data is based on small fraction of all language. Here are some questions that many students never even consider:

- Is the data based on written or spoken language? Maybe both?

- If written language, what were the sources? Newspapers? Novels? Blogs?

- If spoken language, what were the sources? Actual conversations? Chat? Movies?

- Where does the data come from geographically? What time periods are covered?

The answers to these questions matter. Below, I have listed the top 10 characters in two character frequency lists that are obviously based on different sources. Look at them and see if you can draw some conclusions regarding the corpus, i.e. what kind of language was used to generate these lists.

| Rank | List A | List B |

| 1 | 的 | 我 |

| 2 | 年 | 的 |

| 3 | 日 | 你 |

| 4 | 中 | 是 |

| 5 | 人 | 了 |

| 6 | 月 | 不 |

| 7 | 一 | 们 |

| 8 | 大 | 这 |

| 9 | 在 | 一 |

| 10 | 是 | 他 |

While some characters appear on both lists, there are important differences. What do you think List A is based on? What do you think List B is based on? Which one do you think would be most suitable to use as a student wanting to learn basic conversational Mandarin? Think about this for a minute before you check the answer below.

- List A is based on formal, written language, which you can see because of the lack of pronouns high up on the list. The exact source is the Chinese language Wikipedia, which is also something you might have guessed because of the very high frequency of characters used in dates (it could have been any encyclopaedia, of course).

- List B is based on spoken language. More precisely, it’s based on movie subtitles. You can see it’s probably spoken language because people like to talk about themselves and people in their vicinity (hence all the common pronouns at the top). Of course, movies don’t contain naturally produced spoken language, but at least the goal of most movie dialogue is to make it sound as if it were, which is good enough in many cases.

I hope this example has convinced you to not just grab a random list you find after searching for one minute. I will introduce a number of frequency sources in this article and help you choose one that suits you!

Words, characters and components

Unlike other languages, Chinese can be broken down into much smaller pieces while still retaining some meaning. For example, if you take a two-syllable word and break it down, each syllable will be represented in the written language by a character that means something. Often, these characters can then be broken down into components that in themselves also mean something.

Frequency data can be used on all levels, but because of methodological issues, character frequency is what most people talk about. It is, after all, unambiguous what a character is since it occupies exactly one square on a page and it’s easy to calculate frequencies using characters as the unit. However, if you want to focus on spoken Chinese, you’re not much helped by character frequencies, but would much rather use word frequencies. If you focus on learning Chinese characters, you might also want to break down characters into components and see which are the most important to learn first.

In this article, I will introduce frequency data for words, characters and components, in that order.

Frequency resources for the most common Chinese words

For spoken language (and perhaps written language too), words are the most interesting unit, since people use spoken words, not written characters, to communicate. Coming from a language like English, this might seem straightforward enough, just calculate the frequencies of words, right?

Not really. Chinese has no spaces between words, which means that it’s far from easy to figure out where one word stops and the next one begins. 红 (red) is a word, so is 灯 (light), but 红灯 is a word too (red light, as in ” stopping at a red light”). But what about 黄灯 (yellow light)? Or 紫灯 (purple light)? As you can probably see, this is not easy.

What is a word in Chinese anyway?

There are three ways of dealing with this problem:

- The easiest way for students and teachers is to take an extensive dictionary and simply say that everything listed in there is a word, and everything that is not listed isn’t a word. In that case, 红灯 and 黄灯 are words, but 紫灯 is not (I used 现代汉语词典 to check this). There might still be ambiguities regarding which character belongs to which word, though. I don’t know of any frequency lists that use this method.

- Another way is to not care about what actually is a word as defined by linguists, but instead focus on characters that appear together often (called a bigram if it’s a pair of characters) and simply say that that’s a word. The problem is that then things like negated verbs rank very high, such as 不能, 不会 and so on, along with numbers in combination with measure verbs, like 一个.

- The most demanding way is to make sure the texts being used have been segmented into words in some way by a human. Or, more often, a combination of humans and clever tools that help a lot, but which don’t really get everything right. Still, there are often “words” like 不能 and 一个, probably because someone decided that they actually are words for the purpose of the corpus.

So, in essence, while there ought to be a difference between how carefully the material was segmented (if at all), there really isn’t that much of a difference. In case you want to know more about how words are composed in Chinese, check this article: The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words:

The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

8 great resources for looking up the most common Chinese words

We’re now ready to look at the available resources for word frequency in Chinese. I have tried to put broadly useful resources at the top, but haven’t paid close attention to exact ordering:

- SUBTLEX-CH (movie subtitles) – This list is based on Chinese movie subtitles and is thus as close to natural spoken language as you can get. 100,000 simplified words without definition or Pinyin, You will find some 这个 and 不能, but should still be very useful. Note that there are two files, one for character frequencies and one for word frequencies. Article describing the underlying research project here.

- K-5 Word Frequency Dictionary for Chinese L2 Learners – This list is somewhat unique in that it draws on materials for people who learn Chinese as a second language, i.e. textbooks, graded readers and so on (read more about the methodology here). The site presents a search interface, but you can also download Excel spreadsheets. Simplified Chinese with Pinyin. This list comes very close to what I would consider most useful for second-language learners.

- BLCU balanced corpus frequency lists – These lists are based on a ridiculous 15 billion (simplified) character corpus, composed of news, literature, blogs and much more. It is probably the biggest, most comprehensive dataset available. You can access the corpus online here and read more about the project here (in Chinese). The ZIP file linked to above contains text files for each part of the corpus, as well as a global file. If you can’t view the text files, a user over at Pleco’s forum posted UTF-8 encoded versions that work well for me. The lists contain some oddities, such as 第 coming out on top and some kana from Japanese showing up; please see the discussion over at Pleco for cleaned-up versions if you want to remove these.

- University of Leeds: Internet Word Frequencies – This frequency list is based on the Leeds Corpus of Internet Chinese (90 million tokens from 2005). Simplified characters with no frills. You can search the corpus directly online, which is handy.

- 6000 Chinese Words: A Vocabulary Frequency Handbook, by James Erwin Dew – This is one of the few books I recommend. It lists words with traditional characters, but since it’s a printed book, you can’t do much analysis of your own, it does have the data both in alphabetical order (good for looking things up) and in frequency order. It also offers lists of prolific characters, meaning characters that are used in common Chinese words.

- Mandarin Chinese Word Frequency Dictionary – This list presents word frequencies based on the Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese, “balanced” meaning that it draws from several different kinds of texts. This list uses traditional Chinese. The data here is very useful, but it’s not very accessible because it’s in PDF format and not sorted by frequency. While being a bit vague, it seems that the Wiktionary frequency lists are based on this material, and those are much more accessible. There is also an Excel file accessible through Wayback Machine here.

- Leiden Weibo Corpus (and related frequency data) – This list is based on Weibo messages, which makes it interesting for informal writing (and indirectly speaking). It also has a rather unique feature in that messages are coded for which city/province they were posted from. However, to make the most of this resource, you need some database and/or text manipulation skills. The word list is pretty straightforward, but not sorted by frequency. To get the geographical breakdown, you need to combine the word IDs in one file with the actual words in another, so not for the idly curious. Simplified characters, of course.

- Jun Da: Bigram frequency list of the general fiction sub-corpus – As the name indicates, this is an analysis of pairs of characters occurring together in the general fiction part of the corpus used by Jun Da. See also Bigram frequency list of the news sub-corpus. Both are somewhat configurable (you can set frequency and mutual information values) and spit out simplified characters (varying numbers depending on what values you set, of course).

Pew, that’s a lot! Have I missed anything, including easy-to-access derivatives of the above? Leave a comment!

9 resources for checking the most common Chinese characters

As I mentioned above, character frequencies are very easy to obtain (no segmentation needed) and there are numerous lists available online. The only thing you might want to care about is that they are based on a large enough corpus and that the sample roughly matches what you’re after and isn’t very specialised in some area you’re not interested in. I have tried to order them with the most useful at the top:

- Jun Da Chinese text computing: Character frequency list of Modern Chinesea – This list from 2005 is based on written Chinese (both fiction and non-fiction). It contains 10,000 simplified characters, with Pinyin and definition. The same data is also available as two separate lists, with one for fiction and one for non-fiction.

- SUBTLEX-CH (movie subtitles) – This list is based on Chinese movie subtitles and is thus as close to natural spoken language as you can get. 6,000 simplified characters without definition or Pinyin. Note that there are two files, one for character frequencies and one for word frequencies. Article describing the underlying research project here.

- Patrick Zein: The most common Chinese characters in order of frequency – This list is based on Jun Da’s research, but contains further explanations, as well as definitions for variant pronunciations. 3,000 simplified characters, but with notes about traditional usage. Uses GB2312 encoding, which might cause problems for some. PDF version available here.

- Hanzicraft: Chinese Character Frequency List – Around 6,000 simplified characters without definition or Pinyin, but with clickable links to more information about each character. Not specified what data this list is based on.

- Chinese Character Frequencies (Chinese Wikipedia) – This is the list used in the introduction to illustrate the results of using different datasets. This one is based on Wikipedia. 10,000 traditional characters without definition or Pinyin.

- Jun Da: Character frequency list of Classical Chinese – Same as the first resource listed, but for Classical Chinese (i.e. not based on texts in Modern Chinese).

- 6000 Chinese Words: A Vocabulary Frequency Handbook, by James Erwin Dew – This was mentioned already for its word frequency lists, but I include it here as well for the list of prolific single characters.

- Far East 3000 Chinese Characters Dictionary – This book lists 3000 common traditional characters in alphabetical order (which makes it much less useful). It does contain example words and has a layout that is quite inviting. I wrote about using this dictionary in an earlier article.

- 國語辭典簡編本編輯資料字詞頻統計報告 – This lists both the most frequent characters and words, based on a balanced mix of sources in traditional Chinese, totalling around two million characters. This is the best resource based on traditional samples I’ve been able to find. Note that the executable file needs to be downloaded and run, which produces a text file that I was able to view properly in Chrome. It’s a self-extracting zip file that should work on most systems but can be a bit fiddly because of character encoding (see Miache’s comment below). Here is an alternative source that allows for viewing in your browser.

Have I missed any useful frequency lists? Leave a comment below!

Chinese characters, character components and radicals

When looking at character components, the problem is similar to that discussed above regarding words. There is no unified definition of what a component is and there’s often more than one way to break down a character.

For example, the character 行 was originally a pictograph showing a road intersection. So, in a sense, it can’t be broken down and should be treated as a component itself. However, if you just look at the modern form, you can visually break the character down into 彳, 一 and 丁. Or take 想 as another example. Do you break it down into 心 and 相 and be done with it? Or do you then break 相 down into 木 and 目 and count each?

In fact, this kind of data is even trickier to deal with than words, because at least there is some consensus of what ought to be a word, it’s just not easy to apply computationally to a large dataset. When it comes to components, it’s even hard to find data!

Frequency resources for learning the most common Chinese character components

As a shortcut, people sometimes use radicals instead of components, but there are many more components than there are radicals, so that doesn’t give the whole picture. Other times, people break things down as far as the result can be written with Unicode, damn the consequences. This leads to frequency lists where single strokes are the most common “components”.

Here’s my list created using the radical approach described above:

Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals

This list at HanziCraft lists productive character components in order of frequency. It was created by checking how often a component appears in breakdowns, weighted by the frequency of the characters it appears in. It’s a pretty good effort if you’re after visual breakdowns.

We also have this list over at HanziCraft, which lists phonetic components. There’s no frequency information here, but they are commonly used, so I guess it’s better than nothing. This list also includes information about how they influence pronunciation, which is nice.

If you know of more extensive and/or scientific lists for character components, please let me know.

Other frequency resources

Other frequency resources

Here are some more frequency-related resources that don’t really fit in any specific category above, but that I thought someone might find interesting:

- This list contains syllable frequency, listing each syllable, with Pinyin and Zhuyin, as well as a sample character. It’s not sorted in order of frequency, but the frequency data is there. Also, please note that the text file is encoded in BIG5, so make sure you select that when trying to open it.

- Here is a frequency list that also lists the number of strokes for each character. Not sure why this would be useful, but there are probably some applications. The same data is also available in another form, sorted by number of strokes (fewest first). Both are traditional Chinese.

What about HSK and TOCFL, don’t those contain the most common Chinese words already?

Yes and no. While frequency of course was taken into account when creating the official vocabulary lists for these proficiency tests, they are not frequency lists in and of themselves. There are many words that appear very early in these lists, but which are rather uncommon. This is as it should be because there are many words that are disproportionally important for students.

However, there are also words that are very common in the language as a whole, and that are either omitted or delayed in the vocabulary lists for HSK and TOCFL. This is more interesting because these might be words you’ve missed, but which are yet rather common and would boost your listening and reading ability if you knew them. I’ve analysed the official lists for both tests in the following articles:

- What important words are missing from HSK?

Conclusion: What’s your favourite resource for the most common Chinese words, characters and character components?

That’s probably more resources for learning and teaching the most common Chinese words, characters and character components than you ever wanted to see! Still, I suspect there are important resources I have overlooked. If you know of one that really should be included here, please let me know in the comments below, and I will update the article!

8 comments

I found a list, fatizi, undecomposable chinese characters, where I do not know, what to do with it. I guess, today I know about 75% of these characters.

https://wenku.baidu.com/view/a941b1e784254b35eefd3483.html

http://www.moe.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2015/01/13/20150113090418639.pdf

The characters should fall in a category like easy characters or possible character in itself components. I found the list by searching for a list of useful components, that are characters of their own. But I haven’t used it up to now, and there ist nothing like a frequency.

That brings me to an other point. You wonder about the usefulness of the number of strokes in a character. You can take this number as a measure for easyness of a character (as a rule of thumb – it’s far from perfect). With that you can create a ranking, that treats both easyness and frequency.

I’ll check out the list you suggested! Regarding number of strokes, I think difficulty is not related to number of strokes at all. More strokes often make it easier to learn a character, not harder, at least for non-beginners. The real problem is not so much to learn a new character, which very likely consists of known components if it has a large number of strokes, but to keep the new characters separate from ones already known. Lots of strokes makes it harder to write, of course, but not harder to remember (in general, there are of course characters with many strokes that are also hard to remember). My comment here assumes that the student already knows the most common components, of course, otherwise characters with many strokes are obviously harder because they contain more unknown components.

OK, learning new characters or words from a list can be done fast and it is not too boring. But they also need to be reviewed several times. Where do those frequency lists provide interesting review material, at the right level, at the right time?

For beginners and intermediate learners I recommend checking out the official word lists over at wordswing, interesting review can be done by playing games, viewing all words on one page etc..

I found this: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Mandarin_Frequency_lists

I think it comes from this: https://ckip.iis.sinica.edu.tw/project/sinicacorpus

I know of that list, but for some reason decided not to include it. I was actually looking for a frequency list from the Academia Sinica corpus, but couldn’t find anything officially published. The list you link to is close, but there’s so little information on how it was produced that it’s hard to know or use properly.

The number of strokes relates to how physical dictionaries used to organise the characters and words. You needed to know how many strokes the characters and radicals within them had in order to find them in the dictionary.

In fact, mentally counting the number of strokes was how we used to memorise characters.

Now, of course, with dictionary apps, pinyin and other faster means of looking up characters is used and stroke number is obsolete.

The executable files from the Taiwan Ministry of Education link are self-extracting zip files. You can open them on a Mac simply by double-clicking on them. I had a bit of trouble with the encoding (Big 5) and had to open in Safari and then use the menu option View -> Text Encoding -> Traditional Chinese (Big 5). Then I could copy and paste out. I mention this in case anyone else has trouble with it.

Thank you for pointing this out! I have added the information to the article itself and referenced your comment.