When we are born, our brains are open to the world of sound and we can perceive differences between sounds we as adults have learnt to ignore. To be able to master our native language as infants, our brains need to be able to sort sounds into categories through a process called categorical perception.

When we are born, our brains are open to the world of sound and we can perceive differences between sounds we as adults have learnt to ignore. To be able to master our native language as infants, our brains need to be able to sort sounds into categories through a process called categorical perception.

Hearing without filters is great before you know what language you need to learn, but for speech perception, categories are needed.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

Speech sounds can usually be arranged along one or more spectra. For example, the difference between Pinyin b (IPA: [p]) and p (IPA: [[ph]) is aspiration, which is related to something called voice onset time, referring to how long it takes the voicing to start after the stop is released.

To get an idea of how voice onset time works, try saying bin and pin after each other with your fingers on your throat. You should be able to feel that the vibration starts earlier for bin than in pin. This is true in both English and Mandarin.

Learning to sort sounds into the correct categories

If the voice onset time is roughly zero, we get an unaspirated stop, such as b in Pinyin (IPA: [p]). If the voice onset time is significantly longer, we get something called aspiration, which would be p in Pinyin (IPA: [ph]). Voice onset time can also be negative, meaning that voicing starts before the release, such as in a voiced [b], but that’s not a phoneme in Mandarin.

Depending on what language(s) you spoke as a child, your brain learnt to sort these sounds into the right categories based on voice onset time. As a native speaker of English, if you heard b repeated with gradually increasing voice onset time, at some point you would start hearing p instead.

The point is that line where you starting hearing p instead of b is different in different languages. Some languages even draw more than one line, meaning that there are three distinguishing sounds along this spectrum. this happens in Korean and Thai, for example.

Learning to hear new sounds as an adult

As we sort the world of sound into categories, we gradually lose the ability distinguish sounds that either don’t exist in our native language(s) or that are treated as one and the same sound in our native language(s). After all, it’s rather pointless to maintain the ability to distinguish sounds that are not used to distinguish words in the language(s) you speak.

An example of this is the English words “spin” and “pin”, in which the first “p” is unaspirated and the second is more aspirated (it has a longer voice onset time). Many native speakers of English perceive these two “p” sounds to be the same, but in other languages, they are different sounds.

We can learn to create and modify categories when we learn a second language as adults, too, but it requires much more effort and is rarely completely successful. The processes involved here are very complex and not fully understood.

How to really learn Mandarin pronunciation

So, what can we do to make this process easier? The most important thing is to listen to a variety of speakers and pay attention, and do so a lot. Someone first exaggerating a specific distinction (such as that between two tones) and then gradually making it more natural can also help.

Much research has been done into establishing new perceptual categories of speech sounds, some of which I summarised in the article How to learn to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin:

The reason why most students have bad pronunciation

The main reason students typically don’t learn to pronounce Mandarin very well is that they rely on reading more than listening. They look at Pinyin and think that they know what the sounds are like, which means they don’t listen enough and don’t do so with an open mind (to the extent that this is possible).

To add insult to injury, many students just think they know Pinyin, but actually rely heavily on their native language to guess the pronunciation of certain sounds.

Priming your brain to hear the wrong sound

Written letters are treacherous. Most people of course know that the same letter can refer to different sounds in different languages. For example, speakers of English pronounce the capital of France with more aspiration (longer voice onset time) than speakers of French do (voice onset time close to zero), yet the city is spelt “Paris” in both languages. Similarly, if you pronounce Mandarin pīn (as in Pinyin) the same as the English word “pin”, you probably don’t aspirate it enough.

The problem here is that if you start your attempt to learn a new sound withe the letter used to write it down, your brain is already primed to hear the sound you’re used to hearing that letter representing.

Here’s a fascinating example of how your preconceptions can determine what you hear. When you listen to this audio clip that been doing the rounds on social media recently, which word you read (or think about) can determine what you hear:

What do you hear? “Brainstorm”? Or “green needle”? Can you switch between them? Naturally, this aural illusion might not work if your native language is something other than English and it might not work for all speakers of English either. It works for me, though, and it seems to work for a lot of other people as well! What do you hear? Leave a comment below!

So that’s the problem of reading pronunciation in a nutshell. It’s already hard to perceive some sounds, but if you prime your brain to hear something else, it makes it even harder!

Learn Mandarin pronunciation by listening, not by reading

Let’s look at an example from Mandarin. At university, I teach intermediate students that I haven’t had the privilege to teach as beginners. Some of them still pronounce Pinyin shì close to the English word “she”. If given to someone who does not speak a word of Mandarin, that is indeed how most people would guess that shi is read.

But it’s not, and they aren’t beginners anymore, yet many of them still say something close to English “she”. They haven’t realised that there’s something different with this -i. They assume it’s the same sound as in nǐ “you”.

Now, compare this with an approach based mostly on listening, which is what I prefer. When I teach complete beginners, I try to rely on the spoken language as much as possible and avoid even writing Pinyin in the beginning.

Why? Because they will hear what I write, not what I say. They see -i in ni, si and shi and assume they are the same, while they are in fact three completely different sounds. My highlighting that they are different sounds does not always help.

Naturally, focusing only on the spoken language is not very practical in the long run. It’s very hard to create a curriculum without any written content (remember, Pinyin is not allowed either), and it also requires very large amounts of teacher-student interaction, which is either expensive, impractical or both. Most adults also don’t like it when they can’t see things, can’t take notes or can’t look things up on their own.

Open your ears and open your mind

What’s the solution? How can you learn to pronounce Mandarin without being distracted by the written versions of sounds? Here are a few practical suggestions:

- Listen as much as you can. Try to pay attention to minute details in how the sounds are pronounced. Do this a lot and with variation. As I have discussed elsewhere, the brain needs large amounts of data to begin to form the correct perceptual categories, and not just from one speaker. This is what the tone course I built for a research project with Kevin over at WordSWing is for. Spend as much time as you can listening, preferably before you speak. Practising speaking is also necessary, because you need to find the right articulation of these sounds and automate it, but if you aim for the wrong sounds, practising speaking might do more harm than good.

- Use a transcription system that is meaningless to you. The biggest advantage with Pinyin is that it’s very easy to use (you already know all the letters) and that it’s super fast to write, type and read. But as we have seen, this familiarity means that it’s possible to cheat (indeed, it’s impossible to not cheat), and just assume that the final in shi is pronounced the same way as that in si and ni, or that the initial in jī is pronounced liket he “j” in “jeep”, while none of them is. One solution to this problem is to use a system like Zhuyin, which uses symbols that mean nothing to most learners. This forces you to listen, because you really can’t guess how these are pronounced. I wrote more about using Zhuyin and other transcription systems in this article: Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

- Learn the transcription system you use really well; never guess. I can’t stress this enough. All transcription systems that are widely used can be used to fully represent Mandarin pronunciation, but you have to understand that the written symbols, whether they are letters or other symbols, are only labels. They are used to label a category of sounds, but they don’t describe the sounds in that category. This labelling is rarely fully transparent, meaning that a certain symbol doesn’t always represent the same sound, and that one sound can be written using several symbols (the International Phonetic Alphabet being an exception). One of the questions I answered in this article actually deals with this specific question: 9 answers to questions about Pinyin and pronunciation

- Learn the theory behind the sounds. It’s debatable whether or not explicit knowledge about pronunciation improves one’s pronunciation directly. For example, does knowing the difference in voice onset time for the word Paris make a person better at pronouncing the word the French way? Maybe. But theory doesn’t need to be intentionally applied to be useful, it can also help to direct your attention, which certainly can help to adjust your mental model for what these phonemes are supposed to sound like. For example, just by knowing what voice onset time means, and that there’s a significant difference between English and French, will enable you to focus on the right part of the word. Without that knowledge, you might maybe only hear that it “sounds French”, but have no clue what makes it so. If you’re good at mimicking, you can probably pick this up anyway, but not all people are endowed with great mimicking skills. If I’ve experienced one thing since I started studying phonetics fifteen years ago, it’s that I’m much more conscious about sounds nowadays and pay much more attention to details, including in my native language. Read more about the importance of theory here: How learning some basic theory can improve your pronunciation

How learning some basic theory can improve your Mandarin pronunciation

I’ve been interested in pronunciation for a long time and took almost a full year’s worth of graduate courses in Chinese phonetics when I studied in the master’s programme for teaching Chinese as a second language at 國立臺灣師範大學.

I’ve also taught and coached students in this area for years, collecting a large repertoire both common student problems and ways of solving them. Most of the research I’ve conducted myself has also been in this area, most in the area of tone perception.

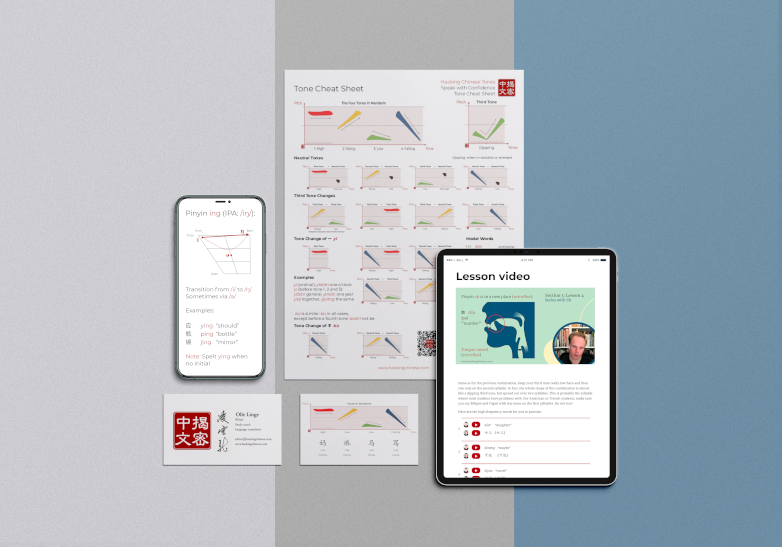

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

Now I’ve taken all that knowledge and distilled it into a course aimed at Chinese students on all levels. This means that it gives all the information and materials a beginner needs, but that it also contains the guidance more advanced students need to fix problems with their pronunciation.

You can find out more about the course below. If you found this article interesting, you’re going to love the course! If it’s not currently open for registration, you can sign up for a waiting list to get notified when it becomes available next time!

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

6 comments

The problem is Pinyin. People read the Latin letters and naturally assume that the phonetics are the same as English (or their language). This is wrong, but it is an unquestioned assumption and Mandarin teachers are absolutely terrible at correcting it.

How many people know that Pinyin “y” is purely ornamental and has no pronunciation? Exactly. And yet people say “yin” and “yang” with the y pronunciation.

The second problem is more advanced teachers assume everyone understands professional linguistics so they throw around terms like fricative and labial and IPA symbols without bothering to explain them.

Yes, I agree! The first part is kind of the point of the article. Either you learn Pinyin properly or you use a system which doesn’t allow you to cheat. Since most people want to use Pinyin, the only sensible option for most courses is to actually teach Pinyin. This is what I will do in the pronunciation course, which also explains the phonetics and at the most important parts of IPA, so hopefully addresses the second part of your comment as well. 🙂

But many sounds in Chinese don’t have corresponding representations in English, and even if they did they’d then be wrong for speakers of other languages. Besides, learners of Spanish or French seem to manage fine despite the same letter representing different sounds, so I don’t think pinyin is the problem per se, but simply that students haven’t been made aware of the correct pronunciation.

Lots of zhuyin courses teach zhuyin by relating each letter to its closest English or pinyin equivalent, so be careful of that!

Yes, good point. That would then almost entirely remove the main benefit of using a system like Zhuyin from a pronunciation perspective. 🙂

Have you tried The Fluent Forever method/app? Having completed the pronunciation portion, I can confidently say I have pinyin more or less down and am ready to begin extensive listening. I certainly know the difference between nī and shī. I think the FF does a great job at letting one acquire spelling and pronunciation rules while also learning IPA.