I first met Scott Young in 2014 in Taiwan when he was doing his year without English, spending 100 days learning Chinese. I gave him some advice about learning and helped him with pronunciation, then did an interview with him towards the end of his learning project. He eventually managed to reach a decent level of Chinese in 100 days, passing HSK 4. We’ve kept in touch since then, and he hasn’t abandoned Chinese, quite the opposite. Scott recently published a book called Ultralearning, and in this guest article, he’ll talk about principles for effective learning, useful for mastering any difficult subject.

Five years ago, I wrote a popular guest post for Hacking Chinese about how I was able to get to a comfortable speaking level (and pass the HSK 4) after just 100 days in China.

Since that time, I’ve continued to improve, and two years ago I was even able to go to Beijing and give speeches in Chinese about my book and answer questions from reporters and audience members.

Over the last few years, I’ve been researching and writing a new book, Ultralearning, about the process of teaching yourself hard skills (such as Chinese). Doing so, I got a chance to dig into the research behind learning and found common principles that make it possible to learn hard things well.

In this essay, I’d like to share these principles, as well as how not following them leads to some common mistakes. Those mistakes, in turn, can prevent you from reaching a decent level of Chinese despite years of study.

Let’s jump in…

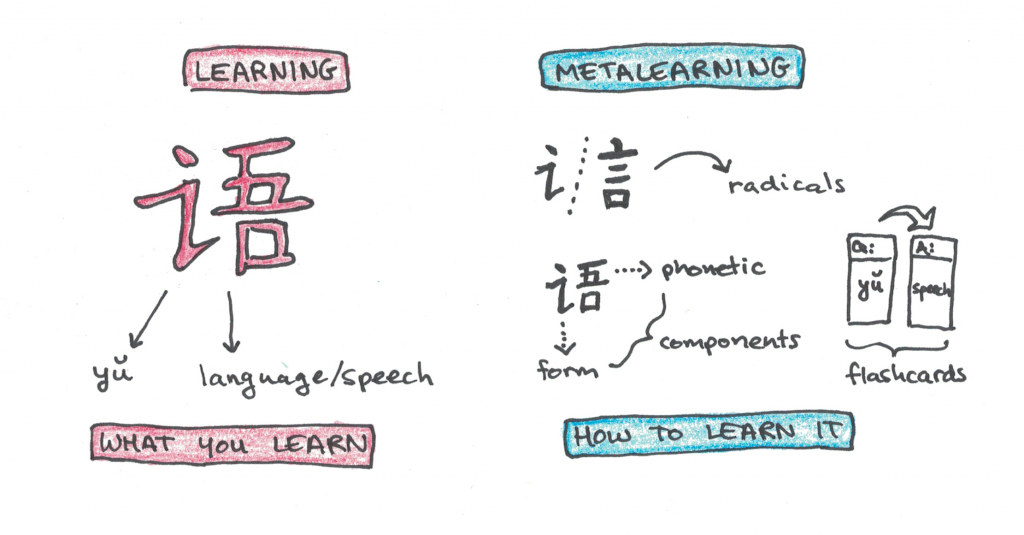

Principle #1: Metalearning — Mistake: Not spending time learning how to learn Chinese

Learning Chinese is a lot of work, but that work can quickly lead to a dead-end if your learning time is invested in the wrong way. The surest way to avoid this mistake is metalearning, or learning how to learn a subject, rather than just the content of the subject.

This principle, metalearning, is particularly relevant to Chinese because there is so much to learn. It’s easy to get trapped learning the wrong things if you don’t structure your efforts the right way.

Learn the right way to position your tongue to properly pronounce the sounds. Learn how characters break down into different functional components. Learn how to memorize vocabulary and how to keep those words from slipping out later. Learn the right way to start reading, listening and having conversations.

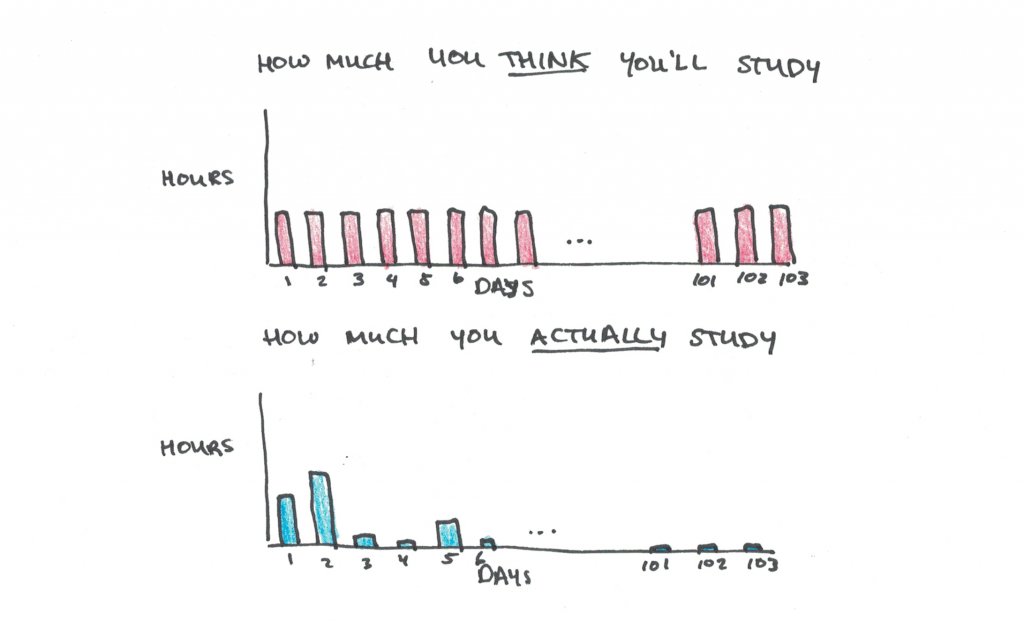

Principle #2: Focus — Mistake: You don’t set aside time to practice

Learning a language is about how many hours you invest, not how many years. Yet a lot of new students get into a trap where they stress and worry about learning Chinese, without actually devoting enough time to learning.

Focus is the second principle of learning, and in order to concentrate on learning, you actually need to put in the time.

I’ve found there’s two main ways you can accumulate hours in Chinese to make significant progress. The first is through immersive bursts. If you have the opportunity to live or work in China, making the commitment to speak Chinese either exclusively, or only with certain allowable exceptions, will immediately boost your total practice time by a large multiple.

The second is through long-term habits. Having returned from my trip, studying Chinese was no longer at the forefront of my life. However, by setting up a habit to read and listen just a little bit, every day, along with a weekly meetup to practice speaking, I was able to keep getting better even after my travel ended. A good habit, extended over time, can accumulate more hours than forcing yourself to study sporadically.

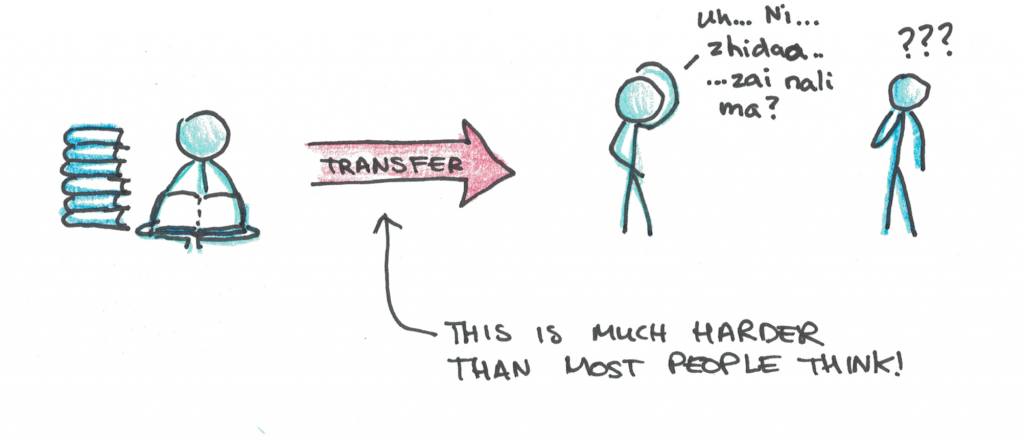

Principle #3: Directness — Mistake: You don’t ask yourself how you’re going to use Chinese

One of the most unsettling things in the scientific literature on learning is the problem of transfer. Most of us assume that knowledge acquired in one place, say a classroom, will automatically transfer to the real world. Yet, the research shows this is much harder than is typically assumed.

This can result in a lot of frustration in learning Chinese. You spend a couple years studying in classrooms, and then you join a meetup or travel to China, and you struggle to communicate. It can lead to the feeling that Chinese is just impossibly difficult, when in reality you may have been learning the wrong way.

The best way to start learning is to always ask yourself how you’ll use the skill or subject you want to learn. Having done that, you can make sure you do some practice that matches it from the very beginning.

If you’re trying to learn Chinese to have conversations in Mandarin, for instance, you ought to have simple conversations (even if they involve a lot of stalling to look things up) quite early on. Instead, many students spend years learning to handwrite characters, even though this is a relatively disconnected task from the one of actually speaking. Calligraphy is great, if that’s your goal, but if your goal is conversation, it’s going to have transfer issues to apply it to speaking.

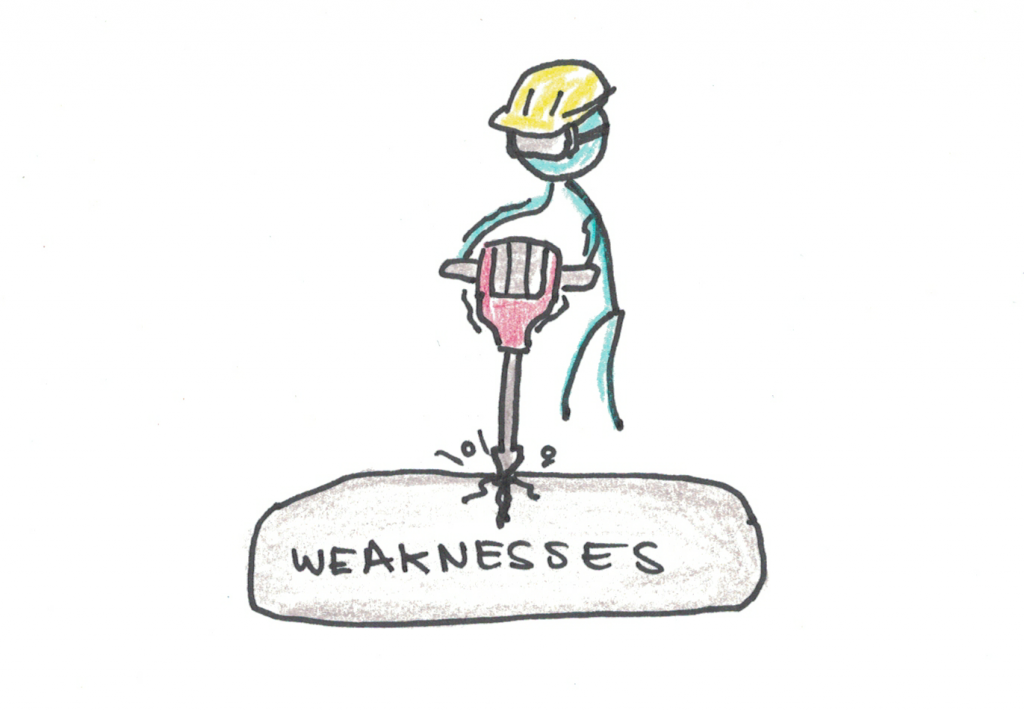

Principle #4: Drill: — Mistake: You don’t work on your weakest points

Learning any language is complicated, especially Chinese. When you’re using the language you need to juggle grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary. You need to parse the words spoken from sentences, often when you can’t exactly hear the tones. The person you’re chatting with may even have an accent that causes you to mishear one word for another.

These difficulties can be overwhelming to start. It can often feel as if Chinese is simply impossible and that you’ll never be able to fluently converse or understand sentences.

The truth is more mundane. There are just too many things going on, and you lack the stored patterns in memory to be able to process it in time.

Luckily there’s a solution: drill. Break apart the things you struggle with and work on them separately, always making sure to reintegrate them back into real situations after. If you lack vocabulary, work with flashcards to add more. If your pronunciation of tones is weak, do tone drills. Can’t understand what people are saying? Practice listening with a podcast, going over the same one multiple times.

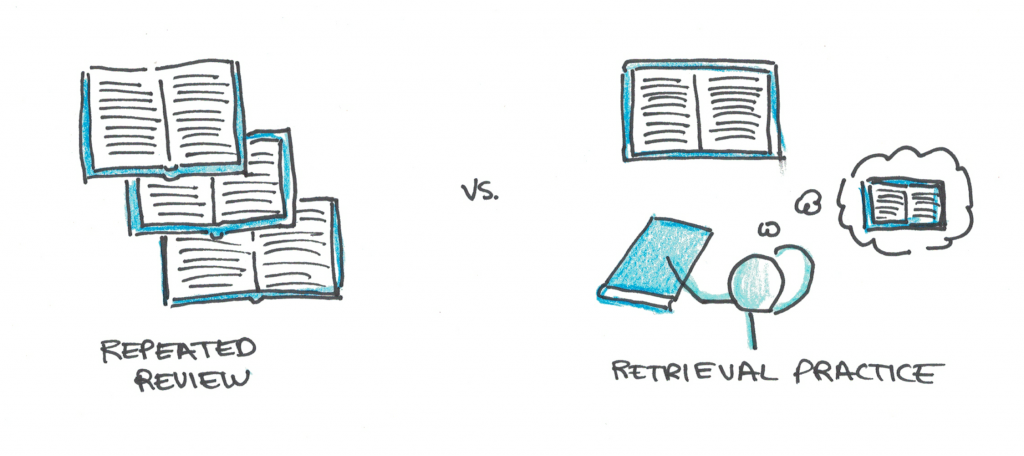

Principle #5: Retrieval — Mistake: You use review instead of retrieval

Retrieval is another important principle of learning. Numerous studies show that attempting to retrieve information from memory will strengthen memory much better than simply reviewing the information on paper.

In one such study the researchers Jeffrey Karpicke and Janelle Blunt broke students into multiple groups. One group they asked to repeatedly review the material, reading it over and over again. Another group they asked to do free recall, meaning they closed the book and tried to recall it from memory without looking again.

Immediately after, they asked each group how well they thought they learned the material. The repeated review group thought they had learned it the best. In fact, the study proved the exact opposite: those who did free recall actually performed much better.

This study shows we’re often deceived at what we actually need to do to learn things well. We review, when we ought to recall.

What this means for learning vocabulary, practicing grammar or doing anything else in Chinese, is that if you actually need to be able to produce the words, sentences or characters, you need to practice producing them, not just look over them in your textbook. The latter may lead to the feeling of learning, but that feeling is usually a lie.

Principle #6: Feedback — Mistake: You get the wrong feedback.

Feedback is also important for learning. Few people would avoid getting feedback deliberately (although many students inadvertently slip into studying in a way that has almost none).

However, equally important as getting feedback is knowing what kind of feedback you’re getting. There are at least two types of feedback worthy paying attention to when learning Chinese: corrective and informational feedback.

Corrective feedback is when someone not only tells you what you’re doing wrong, but what you should have done instead. Are your tones sloppy? A teacher can tell you what sounds you should have made. Is that the wrong word? Here’s what you should do instead. Recently, I got corrective feedback because I was conflating the words 完美 (wánměi) and 完善 (wánshàn). I thought they both meant “perfect” as in an adjective, when really, 完善 means “to make perfect” as a verb. This was helpful feedback and I stopped making that mistake.

However, sometimes you need to be careful. Learners often assume that native speakers have perfect knowledge of their own language. This can lead to traps where you will get explanations of grammar or vocabulary that are completely wrong. Native speakers speak fluently, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they understand the rules explicitly.

An example of this, I was once told that the second 了 in the phrase 我买了苹果了, meant that after buying the apples you ate them! This was from a Mandarin teacher, but it’s a ridiculous explanation. The truth is more subtle, and so often speakers will incorrectly generalize a rule that they understand subconsciously.

Therefore, when getting feedback, pay attention not only to what people are saying, but what they’re capable of saying when giving feedback. Don’t overcorrect just based on one opinion.

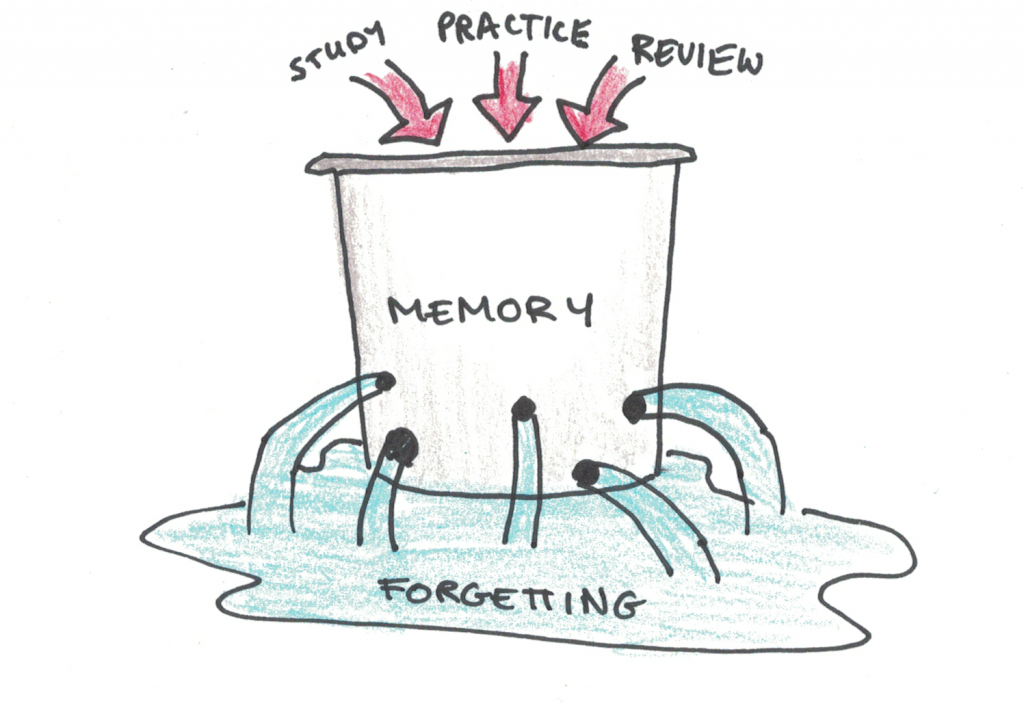

Principle #7 Retention — Mistake: You forget what you’ve learned

Forgetting, and forgetting a language in particular, are perennial problems that face all would-be multilinguals. The human brain seems quite adept at losing skills and knowledge that aren’t in active use.

There’s two ways to prevent this problem when learning Chinese.

The first is to apply spaced repetition systems. This is particularly useful in the early stages of learning, when consuming actual media or having regular conversations is too difficult. This can also help you get through the first few hundred (or thousand) characters and ensure that they’ll be in memory when you need them.

The second is to set up regular sessions for practicing, even when studying Chinese isn’t your main priority. I currently apply two different habits for maintaining Chinese. One is a 10-minute per day habit for reading/listening. This may not sound like much, but it guarantees that I start using Chinese at least once per day, so the total amount of time is often larger.

The second habit I have is regular practice. In my case, I have a Chinese meetup I attend 2-3 times per month, where I can converse. If you don’t have such a meetup in your area, I recommend setting up a regular conversation session with a service like iTalki.com. This can allow you to extend the longevity of your linguistic skills for years with just an hour or two per month.

Principle #8: Intuition — Mistake: You see fluency as magic rather than the product of systematic learning

Okay, few people genuinely believe that fluent speaking is literally magical. However, it’s very seductive to fall into the trap of feeling that there must be something else going on besides just learning a lot of patterns. After all, how do native speakers possibly follow those sentences? How do they distinguish those words? Recognize thousands of characters? Produce the right tones when speaking so quickly?

The combination of all these things can quickly lead you to believe that there must be something else. Some kind of magic that leads to fluent speaking that you haven’t mastered.

Once again, the truth is a lot simpler. Fluent Chinese is the result of thousands, probably tens of thousands, of patterns stored in memory. Not just memorized words, but “chunks” of knowledge where different elements of the language get associated and bound together.

Chunks are the reason why WFMBWBAIW is harder to remember than FBI, MBA and WWW. The first is nine random letters, the latter are three “chunks” you already have stored in memory. If I said the first one out loud, you would think it was very hard to remember it, yet the latter one is easy, even though they have exactly the same content.

Learning a language is the same way. It feels magical because everyone who speaks it well has enough chunks that the things that look like random components strung together to you are only a few recognizable patterns to them. Build those patterns, and it gets easier to do things that previously looked like magic.

Principle #9: Experimentation — Mistake: You do the same thing over and over again, expecting different results

In some ways, learning Chinese is an exercise in extreme patience. You need to systematically learn vocabulary, grammar, phrases and cultural knowledge that slowly stitch together the understanding you need to become a fluent speaker.

Sometimes, however, this patience can become a vice if you end up spending years doing something that doesn’t actually make much progress. One way to avoid this is to avoid falling into the other eight traps I’ve mentioned earlier. Study how the language works, allocate time, learn directly, focus on your weak points, retrieve instead of reviewing, get the right feedback, create systems to retain memories and build patterns that will lead to fluency.

However, the most important thing when learning is to monitor your own approach and detect when you’re going off course. Without this attitude of experimentation, you’re driving blind, and small mistakes can accumulate to a point where you’re no longer making the progress you’d like to.

I think variety and experimentation are critical for handling something as challenging and immense as Chinese. Spending all your time with characters? Try having some conversations. Is your listening ability outpacing your speaking ability? Maybe work on increasing your vocabulary by doing direct practice. People don’t understand you properly? Work on your pronunciation.

If you take charge of your own learning process you can steer yourself to your destination much better than if you blindly follow guides created by others.

Thanks to Scott for sharing these common mistakes and the principles behind them. If you want to know more about how you can use these principles to master other things, go get Scott’s new book, Ultralearning. You con also buy it directly from Amazon here. If you were impressed by Scott’s progress in Chinese in just 100 days, you should know that learning Chinese is just one of many ultralearning projects he has embarked on. Among other things, he also finished a four-year MIT computer science program on his own in just one year. His new book is the culmination of more than a decade dedicated to finding better ways of learning, so you should really check it out!

3 comments

Hej Olle,

Thanks for the article, as well as all the others on hackingchinese.com (althought I haven’t read them all!)

One small comment: You point out the differences between ‘corrective and informational’ feedback. You explain corrective, but you don’t seem to point out ‘informal feedback’.

I agree with you it’s useful to learn ‘chunks’. Words are combined into patterns, i.e. fixed expressions, and so they can (1) create context to improve understanding as well as (2) possibly enhance the speed of learning because chunks provide more learning than just the elements they’re made of, and show how these elements are used in real life. In my learning notes I have started to highlight such fixed expressions: since they’re often quite common you may easily forget to realise they’re fixed expressions. e.g. ‘to restart + a computer’, ‘to take + precautions’.

In a way, it’s never been so easy to learn Chinese (or other things of life) with so much information being available online: websites, YouTube, (e)books, apps… I find it easy to drown in the information available! It’s important to stay focused and try to finish some tracks, on the other hand it’s always a good idea to dedicate some time exploring new information. Yet, the fact that by far most information is produced in English may add complexity for people who aren’t native English speakers.

My last point is that the task of organizing my notes takes a lot of time in itself: to learn characters I prefer to write them on paper, many other texts I’ll input them in a digital way. It’s often a slow process, although speed isn’t as important as just the learning experience itself, I find. It’d be interesting to hear how other Chinese learners go about organizing their notes.

Thanks, once again.

My bad! Informational feedback means it provides information, but not a correction.

So if someone gives you a confused stare when you’re talking to them, they’ve given you feedback, but you don’t know what you should have said differently, or what the correct word is. The point about feedback is that we often get corrections that turn out to be wrong (or sometimes unhelpful) so it can be misleading.

I, for instance, have been told *many* times that the way I describe my profession as a writer is wrong. Some people don’t like 作家 thinking it’s too presumptuous and haughty and have suggested 写手. Others have said they don’t like 写手, as it makes them think of someone who cheats for others on exams. The point is that even native speakers can disagree about the correct use of a term, and many native speakers aren’t always aware of the rules that underlie grammar or phonology, so you need to be careful.

Somewhat tangential, but I wrote an article about things that are commonly taught but which are incorrect. Not sure if you’ve seen it already, but you might find it interesting: 7 things you were taught in Chinese class that are actually wrong.