There is a lot of talk about the f-word in the online world of language learning.

- What does it mean to be fluent?

- What is the best way to become fluent in a language?

- How fast can you get there?

I find these questions interesting, and I have discussed the second and third questions in some detail, but today I am going to talk about another word that carries even more weight: mastery.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#233):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Fluency and mastery of Chinese

In my opinion, fluency simply means that you can communicate effectively using the language you have learnt. A beginner can be fluent if they know how to use what they’ve learnt well, but you can also study Chinese for a long time without being fluent. Fluency, in other words, is about how well you can use what you know.

Mastery is what I call the end-state for second-language learners. It’s not about being able to communicate effectively in specific circumstances, but about an understanding that is both deep and broad, something we can only hope to achieve after many years and tens of thousands of hours of engagement with the language.

While this sounds daunting and might also seem very distant to many of you, I do believe that the principles that will lead to mastery are relevant for intermediate students, and even beginners, too.

Mastery means near-native proficiency in Chinese

As second-language learners, mastery is similar to achieving near-native proficiency, although what native and non-native speakers know will always differ. It’s hard to match the intuitive grasp of syntax and phonology of a native speaker, but there are many other areas of the language to master.

For example, I think I can claim mastery of English to a certain extent, but I’m clearly not a native speaker. My English doesn’t sound as relaxed and comfortable as most native speakers but on the other hand, I think my written English is okay.

My written Chinese is not nearly as good as my written English, but my spoken Chinese probably sounds more natural than my spoken English, considering how much more I have spoken Chinese than English in my life.

Can we reach mastery as second-language learners?

Can we reach such a level as second-language learners? I think so, even though it will always be hard to match the intuitive feel for colloquial language that native speakers have, as well as the more emotional and connotative aspects of words.

I think we can achieve clear and easy-to-understand pronunciation, but truly mastering intonation and tones is very difficult. The same is true for grammar.

That does not bother me, though. I think we can come close enough. If we want to.

Let’s look at how to do that!

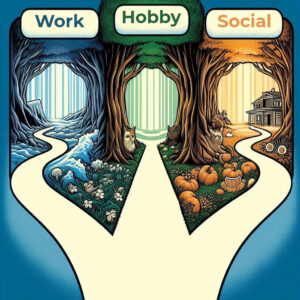

There are only three roads to mastering Chinese

Below, I argue that there are only three roads to mastering Chinese. This might sound like a small number. Should there not be many different ways? No, I do not think so.

The important thing to understand is that mastery requires a truly massive time investment, far exceeding a normal university degree or the ten thousand hours Malcolm Gladwell talks about.

Given this, we need very strong intrinsic motivation to keep spending time with Chinese. I have only come up with three different ways of achieving this, but if you can think of something else, feel free to leave a comment!

The first road to Chinese mastery: Using Chinese in your job

The first road to Chinese mastery: Using Chinese in your job

If Chinese is an integral part of your job and you encounter native speakers daily, you are sure to learn a lot of Chinese. Naturally, you will learn more if you study a bit on the side too, but the exposure and practice you get will accumulate over the years, even if you do not study.

Most people spend perhaps one-third of their time either working or on work-related activities, so if this involves Chinese, you will reach 10,000 hours and beyond in no time.

My experience of using Chinese in my job

My case is a bit special here since I work more with Chinese than in Chinese. For instance, when I write articles like this one, I do not learn any Chinese. Producing a course about listening comprehension in English doesn’t improve my Mandarin either.

Still, teaching is a very powerful way of learning. I learn a lot from students’ questions, and my own studying is largely guided by what I feel is difficult to explain. Teaching Chinese is a good way of learning Chinese, especially if you have Chinese colleagues!

I also teach professional development courses and seminars in Chinese, mostly for native speakers. Unfortunately, Mandarin is a relatively small language in Swedish schools, so this is rather limited. If I did this full-time, I would fully qualify for this road to mastery.

I wrote more about what I do for a living here: How I learnt Chinese, part 7: Teaching, writing, learning.

The second road to Chinese mastery: Cultivating a genuine interest

The second road to Chinese mastery: Cultivating a genuine interest

Some people spend more time on their hobbies than they do on their jobs. If you can make Chinese the target of such a strong interest, you are likely to reach mastery sooner or later. This will power all kinds of useful processes, such as turning most of your life into Chinese.

With a strong enough interest, you will read and listen more in Chinese than you do in your native language. If you enjoy learning Chinese for its own sake and regard it as genuinely interesting and worthwhile, investing tens of thousands of hours is not impossible over a decade or two.

My experience of cultivating a genuine interest

I only partially qualify here. Chinese is not the most fascinating thing in the world to me, and I have too many varied interests, such as gymnastics, reading, solving Rubik’s cubes, language learning, running, gaming, and personal development, to focus solely on Chinese.

Still, I have a tendency to become really interested in something for a few years and then switch focus. Chinese is something of an exception, because even though I have switched interests a few times, they have often remained related to the language.

For example, I was obsessed with pronunciation and phonology for many years, but in recent years, I have become more focused on input, especially listening comprehension.

The third road to mastering Chinese: Having your social life in Chinese

The third road to mastering Chinese: Having your social life in Chinese

In the draft of this article, this third and last road to mastery was called “marry someone who speaks Chinese,” but I found that too narrow.

The point here is that a majority of your social interactions need to be in Chinese. Marrying a native speaker doesn’t guarantee that you’ll learn Chinese, just like moving to China doesn’t mean you’ll learn much either.

Also note that mastery is a lofty goal here. If you only talk about everyday topics with your partner, you will surely become fluent in the areas you communicate in, but you will not reach mastery.

Naturally, marriage is just one way to engage in a lot of meaningful communication. You could achieve the same by having many close Chinese-speaking friends or colleagues. The point is that you need to use Chinese for meaningful communication for a significant part of your life.

My experience of having my social life in Chinese

I am doing pretty well in this area. I have been together with my wife, who is from Beijing, for well over a decade, and we have spoken mostly Chinese the entire time. I also spent four years in Taiwan, where close to 100% of my social life was in Chinese.

I do believe that to truly reach mastery this way, one probably needs to live in a Chinese-speaking environment, though, but this is a topic I’ll save for an upcoming article.

Different roads, different destinations

It should be clear from the above discussion that mastery is a broad concept, including many different skills. The roads I have described are not equal in terms of the skills they develop, or at least that’s not a given.

For instance, cultivating a strong interest doesn’t guarantee mastery in all areas; it depends on what your interest is directed towards. If you’re interested in wuxia novels, this will lead to a lot of exposure to the written language, but you could also talk to people about your reading and write about it in Chinese

The type of job you have in Chinese greatly influences the skills you acquire. Compare my situation with someone working in interpretation or translation, for example. Or someone who works for a company where Chinese is the main language.

Parallel roads to mastering Chinese

Still, I think it helps to think about the different roads to mastery. It is not the case that you must choose one of them, which is partly why I included my own experiences and thoughts above.

The goal here is to show that since we need to spend so much time, we should find ways of doing it that genuinely matter to us. This will make Chinese an integral part of our lives, not just something we study.

There may be other ways to integrate Chinese into your life beyond the three roads I mention here, but, as I said earlier, I believe these are the main ones.

I do love you, but you speak the wrong language

Which road we follow is not always up to us; serendipity and fate also play a role. We can choose some roads deliberately and increase the probability of others, but at the end of the day, some things are simply beyond our control.

Most people, myself included, certainly do not choose their partners based on the language they speak (“Sorry, I do love you, but you speak the wrong language, bye!”). Naturally, if you socialise mostly with native speakers, it is not surprising that you end up marrying one, but this is presumably not the goal.

We have more control over what we work with, where we live, and whom we choose to spend time with, but even these depend on other factors.

Finally, even though we can cultivate and maintain a strong interest in the language, it is hard to create one from nothing or control how we feel about studying Chinese.

The road ahead: Towards mastery of Chinese

Mastering Chinese is no small task, and every learner’s journey will look different. The encouraging takeaway here is that the roads to mastery all involves investing time and energy, not being talented or smart. I genuinely believe that anyone can master Chinese, even if you start learning later in life, you just need to find a road that suits you.

Editors note: This article, originally published in 2014, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in January 2025.

12 comments

Olle,

I really think you should write an article on the mystery of getting better at a language. My greatest improvements have come from moments when I wasn’t trying to go through an SRS deck, or use skritter, or study textbooks, or even going to classes. My greatest improvements came when I was just communicating with native speakers with no intent to learn anything. This happened both when I was in Taiwan and now that I have been in the US for five years. There is something that happens when you let go of “trying” and just embrace the chance to get to know another human being. All the vocabulary and reading and writing seems insignificant to exchanging meaning beyond concepts and words. This is when true mastery happens, I believe.

First of all, I would rather say getting a ‘native-like’ accent rather than becoming ‘accent-free’. Nobody is accent free – if people were accent free, how could I tell the Taiwanese tourists apart from the (northern) Chinese tourists in Japan as soon as they start talking? My English is not accent-free – my accent is Bay Area with an Appalachian flair and overenunciation due to being in Asia for years. I realize this is a nit-pick … but I think the concept of ‘accent-free’ is an obstacle to picking up a native-like accent – for example, if you want to sound like a native, you have to pick at least one native accent to study, which means you have to be aware that accents are not neutral.

Overall, I think this is a great article. I find it difficult to talk about fluency, and I think the distinction between fluency and mastery helps.

I think that, considering my ongoing interest in Chinese books, I will get mastery of reading eventually. However, I think I will get to mastery of writing never, and mastery of conversation only if I get a certain job/kind of social life.

And thank you for saying ‘having your social life in Chinese’ rather than ‘marry a Chinese speaker’. As an aromatic asexual, I really appreciate the inclusion of a diverse range of social lifestyles.

Oh, I meant “accent free” as in “not having a foreign accent”, I don’t think much of what I write applies to native speakers. So, yeah, of course you’re right, I just took that part for granted! 🙂

I second this great piece of article!!! As a language learner of English and Japanese for over the past 18 years (18 years so far for English, 10 years or so for Japanese), I say these are the “right ways” or mindset for achieving fluency, or mastery as all of the language learners dream of.

Mastery is a challenge, and very likely a lifelong challenge, but it is also a possible achievement that worthy of one’s time and effort.

天下無難事,只怕有心人。I wanna be the 有心人 in terms of language learning!!

Hi Olle, I’d be interested to hear more about this:

“I have a tendency to be really interested in something for a few years and then switch focus. Chinese is so far the only exception.”

I can definitely relate to switching interests every couple years. With Chinese, did the interest just stay naturally, or did you have to work to stay interested? Why do you think Chinese has held your interest, and not other pursuits?

Thanks, love your writing!

Hi Paul,

That’s a very good question. I guess part of the reason is that Chinese is more complex and more varied than many other hobbies I’ve had. There’s simply more things you can do and in more different ways. In fact, you can do anything with a language. I think the reason I’ve been into gymnastics for more than a few years now is similar, it’s simply a more complex/complete sport than diving, unicycling, swimming etc.

/Olle

I think the most interesting thing about mastery is that it ins’t a big deal at all, you listen Chinese, there’s Chinese in your PC,in your games,in our browser, in the bookshelf, in your brain, in your thoughts, your’re holding Chinese, and also wearing it. And then after the earth spinning around sometimes you mastered it. And that’s what every human being is doing right now, in our case, we just picked up another language do to it.

This reminds me of a post of a Chinese learner that seemed very deep, he said that he had always saw his Chinese media as means to acquire the language, he never let it flow, let it BE, forget that Chinese exists, forget about all the “language learning” stuff and see and hear the things he wants to without wanting to learn anything, let himself be Chinese. He stated that this thing, most than hanzis or tones, are what separate the natural speakers from the eternal learners.

I could instantly relates what he said with my experience learning English and it made me really rethink the way I looked at Japanese. I now think that’s a 道 in getting used to languages, it’s probably the so called “momentum” and when I looked back I realized I had almost no momentum with Japanese but with English it was every freaking day! I went to see blog’s like this, wikipedia and videos not because I cared to English but because those posts and ideas makes me excited and I can relate them to my life.

I had to laugh when I read your suggestion to marry someone Chinese as a way of learning the language. I’ve been married to a Chinese man for 30+ years and he will not speak Chinese with me. However, I have the opportunity to talk to his relatives, who speak little or no Chinese. Right now I am ramping up my Chinese learning because we’re planning a long road trip in China and I don’t want all the communication burden to be on my husband. Thanks for your interesting articles on this website!

Yeah, having a Chinese-speaking partner is of course no guarantee, it all depends on what language you speak. This article is more about discussing possibilities, but neither of these guarantee success in any way. However, I believe that you need at least one of them.