I first launched Hacking Chinese to answer the question of how I could have learnt in a better way, hence the current tagline “A Better Way of Learning Mandarin”. This typically involved writing about topics that teachers and textbooks tend to neglect, such as how characters work or how to get the third tone right.

I first launched Hacking Chinese to answer the question of how I could have learnt in a better way, hence the current tagline “A Better Way of Learning Mandarin”. This typically involved writing about topics that teachers and textbooks tend to neglect, such as how characters work or how to get the third tone right.

Over the years, as I’ve shifted focus from learning Chinese myself to teaching others or otherwise facilitating their learning, the topics I write about are no longer restricted to just what I happened to wonder about as a beginner, but that’s still where everything began in 2010.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#211):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Giving myself advice as a beginner student of Chinese

In this series of articles, we will pretend that I have a time machine and can go back to advise a younger, less experienced version of myself. We will make three stops: at the beginner, intermediate and advanced levels.

In this series of articles, we will pretend that I have a time machine and can go back to advise a younger, less experienced version of myself. We will make three stops: at the beginner, intermediate and advanced levels.

I will make sure to present my advice in a manner that makes sense even if you’re not familiar with the story of how I learnt Chinese, but if you want to know more about that, check out the following articles:

- Where it all started

- Learning Mandarin in Sweden

- My first year in Taiwan

- My second year in Taiwan

- Returning to Sweden

- Graduate program in Taiwan

- Teaching, writing, learning

It’s notoriously difficult to describe language proficiency, so take the division into beginner, intermediate and advanced with a grain of salt. In very rough terms, I count myself as a beginner during my first year of learning Chinese (parts 1 and 2 above), as an intermediate student from my second year in Taiwan up to applying for a master’s degree program (parts 3 and 4), and finally as an advanced student from then up until now (parts 5, 6 and 7).

In this first article, I will focus on the beginner level. The intermediate and advanced levels will be covered in upcoming articles. Not all advice I will offer will apply to every student, but most of it will be relevant to a large majority.

Here’s a list of all three articles in this series:

- The time machine, part 1: Beginner

- The time machine, part 2: Intermediate

- The time machine, part 3: Advanced

Advice to myself as a beginner student of Chinese: Venture beyond the classroom!

A classroom is a safe place to start learning a language. Everybody knows as little as you do, and the language is introduced in bite-sized chunks at a manageable pace. If you have a moderately competent teacher, learning Chinese is meaningful, interesting and even fun!

But even though classroom learning can be great and can remain useful up to an advanced level, it’s not enough. Confining yourself in the classroom is like practising dry-land swimming or splashing around in the shallow end of the pool when you want to learn to swim; these might be good preparatory steps, but it’s not enough if you want to learn to actually swim.

The problem here is that while you’re in the shallow end of the pool, you feel like you’re doing great. You can perform the tricks in your textbook and jump through the hoops set up by your curriculum, and in the end, you might even get a piece of paper with a nice grade on it.

Yet the day you venture outside the classroom, it all comes crumbling down, and you realise that your Chinese is not as good as you think it ought to be. This is not merely a reflection of real-world Chinese being more chaotic, it’s also because many courses focus on the wrong things and don’t prepare you for the real world. I wrote more about this here:

So, the summarising advice for beginners is to venture outside the classroom. I don’t mean that you should leave it altogether and shut the door behind you forever, just that you should not be satisfied to limit your contact with the language to things carefully presented to you in class.

So, the summarising advice for beginners is to venture outside the classroom. I don’t mean that you should leave it altogether and shut the door behind you forever, just that you should not be satisfied to limit your contact with the language to things carefully presented to you in class.

Below, I will discuss three different cases in more detail to show you what I mean and suggest what you should do instead.

If you want more structured advice for how to get off to the best possible start with your studies, please check out my beginner course Unlocking Chinese: The ultimate course for beginners. If not, no worries, there are 500 articles here on Hacking Chinese, all available for free!

Beginner Chinese advice #1: Go beyond your textbook as soon as possible

A textbook is like a carefully designed house of cards. It relies on what was taught in previous chapters to build up to a more advanced level but won’t spend much time solidifying the foundations. That’s a pity because your proficiency is often more determined by how well you know the things you know, rather than by how much you know.

If you use only your textbook for learning vocabulary and grammar, your knowledge will be full of holes, just like a house of cards. To fill in these gaps, you need to go beyond your textbook.

As if the holes weren’t serious enough, a further consequence of sticking with your textbook is that you don’t get exposed to the vocabulary and grammar you do learn as much as you need to, and not in varied enough contexts either.

Start listening to and reading Chinese outside your textbook as soon as you can

Textbooks are good at introducing completely new language to students, so while you should diversify your reading and listening beyond your textbook, you don’t have to do so from day one. Free listening and reading materials you find online are typically not very well-adapted for zero beginners.

However, as soon as you’ve learnt your first hundred words, you’ll be more than ready to expand. Here are some suggestions:

Get hold of more than one textbook – This is a wonderful way of accessing more Chinese aimed at beginners. Pick up a few extra textbooks and use the audio and text in them in parallell with your main textbook. If you study the same chapters, you’ll encounter mostly words and grammar you already know. I’ve written more about this here: Why you should use more than one Chinese textbook.

Get hold of more than one textbook – This is a wonderful way of accessing more Chinese aimed at beginners. Pick up a few extra textbooks and use the audio and text in them in parallell with your main textbook. If you study the same chapters, you’ll encounter mostly words and grammar you already know. I’ve written more about this here: Why you should use more than one Chinese textbook. Use graded readers – These are books aimed at students on a particular level, usually defined by how many unique characters or words they contain. The easiest start around 100-150 characters/words and should be accessible once you’ve covered the first few chapters in your textbook. Graded readers are great because they become easier the more you use them, not harder like ordinary textbooks! Of course, you can also listen to the texts, even if they are called graded “readers” My favourite graded reader series is Mandarin Companion: Easy to read novels in Chinese

Use graded readers – These are books aimed at students on a particular level, usually defined by how many unique characters or words they contain. The easiest start around 100-150 characters/words and should be accessible once you’ve covered the first few chapters in your textbook. Graded readers are great because they become easier the more you use them, not harder like ordinary textbooks! Of course, you can also listen to the texts, even if they are called graded “readers” My favourite graded reader series is Mandarin Companion: Easy to read novels in Chinese Check out beginner podcasts – There are lots of podcasts aimed at beginners. Most of these aren’t particularly good, because they are mostly in English, but if you can find a podcast you enjoy, this is a great source of extra listening practice. Even if a podcast does contain a lot of English, you can skip these bits and focus only on the dialogue, text or whatever it is they are talking about. You can also read the transcript for reading practice, but do that after you listen. For beginner podcast recommendations, check this article: The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners.

Check out beginner podcasts – There are lots of podcasts aimed at beginners. Most of these aren’t particularly good, because they are mostly in English, but if you can find a podcast you enjoy, this is a great source of extra listening practice. Even if a podcast does contain a lot of English, you can skip these bits and focus only on the dialogue, text or whatever it is they are talking about. You can also read the transcript for reading practice, but do that after you listen. For beginner podcast recommendations, check this article: The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners. Watch beginner videos – The reason beginner podcasts contain so much English is that it’s hard to make the content comprehensible for beginners relying only on spoken Chinese. A better way to get around this is to use images and body language, but this obviously requires video. There is a growing number of great channels on video platforms like YouTube catering to beginners, and many of these use almost no English at all. Here are three of my favourites: Slow and Clear Chinese, Mandarin Click, Bumpy Chinese / Comprehensible Chinese. For a more in-depth discussion about beginner listening ability, please refer to this article: Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how.

Watch beginner videos – The reason beginner podcasts contain so much English is that it’s hard to make the content comprehensible for beginners relying only on spoken Chinese. A better way to get around this is to use images and body language, but this obviously requires video. There is a growing number of great channels on video platforms like YouTube catering to beginners, and many of these use almost no English at all. Here are three of my favourites: Slow and Clear Chinese, Mandarin Click, Bumpy Chinese / Comprehensible Chinese. For a more in-depth discussion about beginner listening ability, please refer to this article: Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how. Explore reading apps and websites – While you can use videos and podcasts for reading practice as well, either with manually created subtitles or with automatically generated ones, there are in fact many apps and websites that focus specifically on reading, and these are usually a better choice. Check out apps like DuChinese and The Chairma’s Bao, or websites like Mandarin Bean and HSKReading.com. For more free reading apps and websites, check The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners. For about beginner reading resources specifically, check The best Chinese reading practice for beginners.

Explore reading apps and websites – While you can use videos and podcasts for reading practice as well, either with manually created subtitles or with automatically generated ones, there are in fact many apps and websites that focus specifically on reading, and these are usually a better choice. Check out apps like DuChinese and The Chairma’s Bao, or websites like Mandarin Bean and HSKReading.com. For more free reading apps and websites, check The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners. For about beginner reading resources specifically, check The best Chinese reading practice for beginners.

That’s a lot of resources, but don’t pick just one of them, use as many as you can, all at once! Discard resources you don’t enjoy using and save those that are too hard for later.

If you’re enrolled in a formal course, you will keep chugging along in your main textbook series, building an ever-taller house of cards. To build fluency and solidify the foundations, it’s essential that you move beyond your textbook!

Beginner Chinese advice #2: Interact with real people earlier

If you browse advice about learning languages online, you’ll find some disagreement regarding the importance of speaking a language early on. Some say that input is all you need, and that output will come later, others stress the importance of speaking from day one.

There’s also some debate about whether you should focus mostly on the spoken language before you start with reading and writing, but in my opinion, listening and speaking should come before reading and writing.

The reason is that there are some grave consequences of neglecting the sounds of the language (listening and speaking), but few downsides to delaying learning to read and write. Read more here: Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Real communication is enlightening and motivating

My stance regarding speaking from day one is that it’s not the speaking itself that matters but communicating and interacting in real-world situations. Listening is more important than speaking, no matter what level you’re on, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use Chinese to communicate and interact with real people.

There are many reasons why you should include real communication in your learning as early as possible. Before I list them, let me clarify that when I say “real”, I mean that there needs to be a genuine exchange of information.

Reading a dialogue with a classmate or saying after your teacher does not count. If you don’t come across real communication naturally, you can create or simulate it.

Here are some reasons why communicating in Chinese is important for a beginner:

- Communication guides your learning – When you speak Chinese with another person, it highlights what you know and what you don’t know. This allows you to identify your weaknesses and work on them. This type of feedback is essential because as a beginner, you cannot evaluate how clear your pronunciation is, how legible your handwriting is and the like. I wrote more about the importance of feedback here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing.

- Communication is motivating – Most people learn Chinese to be able to interact with Chinese speakers, so doing that early on links your endeavours to a real-world goal. Relatedness, or connecting with other people, is also a key factor in motivation. Naturally, this requires the social interaction to be positive in terms of atmosphere and attitude, so do your best to find communicative situations that you feel comfortable in!

- Communication is authentic – When you stick too closely to your textbook, you learn only what a group of authors think you ought to learn, but when you communicate, you’ll learn what you need to talk about topics you care about. The input you receive, at least if the other person is a native speaker, is also authentic. It might be adjusted a bit to suit your level, but it’s not aimed at practising a grammar pattern or a piece of vocabulary. For more about authentic content, check this article: Are authentic texts good for learning Chinese or is graded content better?

- Communication is meaningful – Most teachers and researchers agree that for input to be helpful, it needs to be meaningful and contextualised. Classroom learning is often artificial and devoid of context, but when you talk with real people in Chinese, the language used is firmly anchored in the conversation. It’s also more likely to be interesting to you personally, which motivates you to engage with it and makes it likelier to stick.

- Communication is improved by communicating – Beyond knowing words, grammar and so on, being able to communicate is also to a significant extent about being good at using communicative strategies. You need to be able to ask for clarification, request someone to speak more slowly and navigate the conversation in a myriad of other ways. The only way to get good at this is to communicate a lot. If you want or need to use Chinese quickly, this is extra important. The problem for many people studying in their home countries (like I did) is that there is little or no real communication in class, so you don’t realise its importance until much later.

How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing

Now, this doesn’t mean that you have to rush out and make ten Chinese friends on day one, but it does mean that you should incorporate some real communication with people who aren’t your classmates or your regular teacher. For most people, this will be online, which is fine.

I waited too long before I used Chinese to communicate

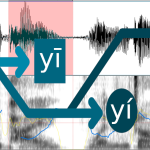

I waited too long before I started using Chinese, which meant it took me longer to figure out some core issues than it otherwise would have. For example, I would have realised earlier that I needed to seriously up my listening game, and I might also have figured out some pronunciation issues earlier, such as how the third tone is actually pronounced.

Exactly how much time you spend with real-world communication (or simulated real-world communication) is up to you and depends on many factors. If you are more of an introverted student like me, you need encouragement to do this at all, but if you find yourself doing this without being prompted, my advice is instead to focus more on listening and reading.

For all the introverted learners out there, I collected my best advice in one article here: 8 tips for learning Chinese as an introverted student.

Other factors that influence your strategy are practical things such as how easy it is for you to find people to talk to, if you can afford to pay people to help you, how soon you want to be able to use your Chinese, and so on.

I don’t know your specific situation, but I waited a year before I started speaking regularly with people outside my classroom. That is way too long, and it meant I lost a lot of potential learning opportunities in my first year. Don’t be like me.

Beginner Chinese advice #3: Make sure you learn pronunciation properly

My final piece of advice might not seem related to venturing outside the classroom at first, but only if you aren’t familiar with the state of Chinese language education across the world.

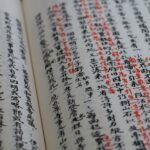

Typically, pronunciation is taught at the beginning of the first semester, sometimes in one big lump at the very beginning, sometimes spread out a bit. You learn Pinyin, you learn the tones, and you think you’re done.

Wrong. You’re not done.

Your journey towards clear and comprehensible Mandarin has just begun. Unless you are incredibly good at mimicking other people and picking up new sounds, what you get taught in a huge majority of beginner courses in Chinese, at university and elsewhere, is woefully inadequate for learning to speak clearly so it’s easy for native speakers to understand you.

This is doubly unfortunate because out of all the things you potentially could delay, pronunciation is the worst. If you skip learning characters early on, you can pick them up later, and you’ll even be better off for it. If you don’t read enough, you can compensate by reading more later.

Learn pronunciation properly from the start and save yourself a ton of trouble later

Delaying pronunciation is not like that, because fixing bad pronunciation is harder than learning good pronunciation from scratch. I have spent a significant part of my professional career working with adults who are willing to improve their pronunciation, usually after having studied for a (sometimes large) number of years. It can be done, but it’s not easy! In contrast, getting pronunciation right from the beginning is significantly easier.

So, my advice is to make sure you learn the tones, initials and finals. Make sure you understand the link between sounds and written symbols, and make sure you know all the Pinyin traps and pitfalls.

Don’t think that just because you finished that part of your course, you’re all set. Don’t think that your tones will naturally become perfect over time if you don’t focus on them, because in all likelihood, they won’t.

A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

I cared about pronunciation, but I didn’t take responsibility for my own learning

During my first year or two, I did care about pronunciation, but I did not realise that to really attain clear pronunciation, I needed to look outside the classroom. This created several issues that took hundreds of hours to fix later.

I learnt a lot by doing that, but it was also completely unnecessary. If I had realised that the courses I took weren’t enough, my pronunciation would have been much better.

I have created a whole course to address this very problem, called Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence, but here are the key components:

Listen and pay attention – This is essential. To be able to hit a target, you need to know what it sounds like. There’s also ample research showing that varied listening to many speakers is necessary to learn to perceive new sounds and tones. Read more about this here: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin.

Listen and pay attention – This is essential. To be able to hit a target, you need to know what it sounds like. There’s also ample research showing that varied listening to many speakers is necessary to learn to perceive new sounds and tones. Read more about this here: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin. Mimic native speakers – There are many ways of mimicking, and you should use all of them. Say after your teacher, read along with the textbook audio, echo in your mind what people say around you. Personally, I think the best way is to use recorded audio to listen and mimic short snippets until you can say it exactly like the native speaker. I wrote more about this in Mimicking native speakers as a way of learning Chinese.

Mimic native speakers – There are many ways of mimicking, and you should use all of them. Say after your teacher, read along with the textbook audio, echo in your mind what people say around you. Personally, I think the best way is to use recorded audio to listen and mimic short snippets until you can say it exactly like the native speaker. I wrote more about this in Mimicking native speakers as a way of learning Chinese. Understand what you’re doing – While it’s not necessary to be a phonetician to learn to pronounce a foreign language as an adult, some basic understanding of how sounds are produced can be incredibly helpful. Naturally, you don’t need to understand how to pronounce easy sounds like m, n, l and the like, but having a basic understanding of tones is essential. The same is true for trickier initials, such as j, q and x. Detailed explanations of all sounds in Mandarin make up the core of my pronunciation course.

Understand what you’re doing – While it’s not necessary to be a phonetician to learn to pronounce a foreign language as an adult, some basic understanding of how sounds are produced can be incredibly helpful. Naturally, you don’t need to understand how to pronounce easy sounds like m, n, l and the like, but having a basic understanding of tones is essential. The same is true for trickier initials, such as j, q and x. Detailed explanations of all sounds in Mandarin make up the core of my pronunciation course. Get feedback – As a beginner, you will not be able to hear if you’re doing something wrong. Using the mimicking method described above, you can often hear if you say something different from the model you’re copying, but you can’t rely on your own hearing to determine how well you’re doing. Get feedback!

Get feedback – As a beginner, you will not be able to hear if you’re doing something wrong. Using the mimicking method described above, you can often hear if you say something different from the model you’re copying, but you can’t rely on your own hearing to determine how well you’re doing. Get feedback!

By realising that what you get in a formal course isn’t enough, you can go beyond that and make sure your Mandarin pronunciation comes off to a good start!

Conclusion: Beginners, don’t get stuck in the classroom!

Those are three pieces of advice I would have given myself as a beginner if I had a time machine. My situation as a beginner wasn’t different from most of the students I have talked to, and I know that this advice also applies to a large majority of beginners.

Maybe a few of you happen to be in fantastic courses with awesome teachers, but that’s still not going to be enough; you need to take responsibility for your own learning, and the sooner you do it, the better!

And for all the non-beginners who’ve read this far, what advice would you offer yourselves as beginners? Please leave a comment below!

In the next instalment in this series, we’ll get back into the time machine to jump forward a year or two and discuss what advice I would offer myself as an intermediate learner. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, if you have questions about learning Chinese as a beginner, I have compiled an extensive Frequency Asked Questions page here: Learning Chinese as a beginner.

https://www.hackingchinese.com/archive-2/beginner/

7 comments

“when your actual goal is to scuba dive to the shipwreck in the deep, shark-infested waters off the coast.”

Is it, though? How many Chinese learners have goals that lofty?

One thing I learned from my studies has been that most pedagogues are scholars, and they assume anyone else studying Chinese has the same goal as them: to go all the way to classical Chinese and study poetry and philosophers in the original. How many learners have this as the goal?

And thus, you can learn several textbooks of material and still don’t know how to say “where’s the bathroom?”

If you raise the issue you are contemptuously told off to “get a tourist phrasebook, this is Chinese learning.”

I assert that most learners are like myself, we want to learn Chinese so we can live and work in China.

There are few or no textbooks for us. Who cares if we can’t read at a university level? It’s assumed that’s what we want.

If I can read menus, the gas bill and all the characters in use on Taobao that’s fine.

That’s a great question! I didn’t mean it as an analogy for how ambitious your learning is, though, more that some types of practice don’t take you closer to certain types of goals. For example, if you stick to dry-land swimming or stay in water so shallow don’t need to or can’t swim there, you won’t get good at swimming. Maybe that’s a better way of phrasing it? The point is not that your goals need to be very loft, but that textbooks rarely prepare you for anything in the real world. I would say that the fact that you can study several textbooks without learning to say “Where’s the bathroom?” (or understand the reply) is a good example of what I’m after here. So yes, I agree with you completely!

I can swim. I can swim just fine. I can spend all day at the lake or swimming pool or ocean and will never wear scuba gear, nor do I ever see any need to. Diving to shipwrecks off the coast? Absurd. I’m plenty “good at swimming”.

I can drive a car just fine and will never enter a rally competition. I’m plenty good at driving.

I think scholars find it insulting to their profession that people like me exist. Because they DO aspire to be at the top and people like me weird them out and make them feel like their credentials and initials after their names mean less.

How many times have we seen the full professor of Chinese who can’t speak Chinese? And then I come along chattering to the shopkeeper she’s struggling to communicate with and fix the problem in seconds. How do you think that makes her feel?

Watch these two Harvard professors sing a song they made to remember the order of the dynasties.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJis9TSw1rE

“knee chang ba”

“Chang zhou Chin Han, Sway Tang Song”

I think/hope I cleared that up in my previous response! The shallow pool and scuba diving to shipwrecks was not meant to map to any scale of Chinese proficiency, the idea was simply to say that doing lots of A (splashing around in shallow water) might not lead to B (swimming, diving), and so sticking to classroom content might not prepare you for what you really want to use Chinese for.

I’m not sure if I’m misreading your comment or if you’re misreading mine, but it seems we’re saying the same thing! The point of this article is to say that if you stick to what your curriculum tells you to do, you will be quite limited in your ability to do things in the real world, such as asking where the toilet is, chat with shopkeepers and deal with authentic interactions in general. They are not completely separate things, but my advice here is to not confine yourself to the classroom, unless good grades is the only thing you’re after.

As for professors who can’t speak Chinese well, I think that is sometimes because they either focused very heavily on the written language (this is very common at universities in the west in general, maybe elsewhere too) or because they started learning long enough ago that access to the spoken language was more limited. In most cases, I think it’s a matter of priority: if their goal is to study Chinese history, tones are probably not at the top of the list of things to master. Then again, if that’s the case, they probably shouldn’t teach language classes either.

Can you imagine a professor of French history who doesn’t speak French?

I think it’s more an issue of “the goal of Chinese learners, as imagined by professors who write the books, is to become a scholar(just like they are) and go whole hog all the way to classical Chinese.”

When I believe my scenario is far, far more common – learning Chinese to communicate with Chinese people and to work and live with Chinese people. This is insulting to these lordly scholars, who feel grossed out by being next to us. Thus being able to learn several volumes of their writings and yet still never learn “where’s the bathroom?”

And when you point this out, they are doubly revolted and reply to put you in your place,” get a tourist phrasebook!” If there’s something these Harvard types despise, it’s receiving criticism from us in the basket of deplorables.

I’ve been a beginner for the longest time hahahaha, and to be honest I’ve enjoyed it a lot. So my advise would be not to compare with the proficiency of others, even though you can’t see improvements you are improving if you are doing the job!!

I used to feel ashamed as how little I was able to speak, since I first started learning Chinese three years ago. But the thing is, if you don’t speak in a regular basis of course you won’t improve your speaking abilities!!!

The things is, I wasn’t been really diligent with my studies at first, and well… life happens!! Beside language learning life has its own difficulties, so to me, as long as I still enjoy the process it’s worth it.

Thanks for such insightful content, it’s always helpful to read or to listen to you c:

Glad you liked the article! I agree with you: comparing with others is almost never a good idea. Other people are not you, they don’t have your background, your study situation, your motivation, and so on, so why compare with them? Compare with yourself! Also, saying that one ought to reach such and such a level after so and so many month or years is obviously problematic. One of my strengths, I think, is that I almost never compare with other people, only with myself.