Regular visitors to Hacking Chinese will know that I’m a bit obsessed with pronunciation and have spent an inordinate of time both on theory (phonetics and phonology in grad school) and practice (improving students’ as well as my own pronunciation). For me it is the most fascinating part of learning a new language.

Regular visitors to Hacking Chinese will know that I’m a bit obsessed with pronunciation and have spent an inordinate of time both on theory (phonetics and phonology in grad school) and practice (improving students’ as well as my own pronunciation). For me it is the most fascinating part of learning a new language.

Naturally, I realise that most students don’t love pronunciation the way I do, and people sometimes ask me why I think pronunciation matters so much.

I could argue the case from a personal point of view, and simply say that I like pronunciation and find it interesting to explore a new world of sound, but that’s not what I’m going to do in this article. Instead, I’m going to look at two arguments why pronunciation actually matters more than you might think, regardless if you like it or not.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

Reason #1: Pronunciation does influence communication

First and foremost, there’s no such thing as having really bad pronunciation in Chinese and still being able to communicate well in a majority of situations. Sure, you can compensate for bad pronunciation in a number of ways, but there’s a limit to how much you can compensate with body language, gestures and close attention to the people you talk to react.

Bad pronunciation does influence communicative ability, but not just in the way you might think. It should be obvious that someone who hasn’t really studied the language might have problems with tones and might pronounce Pinyin as if it were English, but what I want to highlight here is that pronunciation influences communication well beyond the beginner stage.

In short, the more complex and less predictable your utterances become, the more important your pronunciation becomes. If the listener needs to guess what sound you’re trying to produce, it’s going to be harder to understand the ideas you’re trying to convey. This is the core message in The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say. Of course, it’s true not only for tones, but all areas of pronunciation.

The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

This sometimes still fascinates me. I have studied Chinese for about 14 years at the time of writing, and while I think my pronunciation is pretty good, I still make mistakes. Still, in conversations with native speakers, a single tone mistake can throw the listener off in such a way that they fail to understand what I’m saying. This is even though the rest of the sentence is error-free in terms of grammar, word choice and pronunciation.

You’d think that context should make it obvious, but at an advanced level, the opposite can happen, i.e. that people trust you to say the right thing so much that when you don’t, they really don’t understand what you’re saying. These problems are of course much more common for beginners and intermediate learners, I’m just pointing out that it affects my ability to communicate too.

Why bother improving my pronunciation? If can make myself understood, that’s enough!

This is a very common attitude I’ve heard from many students, which I think is misguided and presents a false dichotomy. You can’t just say regard pronunciation and communication as two different things, and then conclude that “communication is enough”.

All mistakes in a language affect communication in some way. If you make one mistake in every sentence, you can probably get away with it (except when you can’t; see above), but since it’s very unlikely that your grammar, word choice and delivery are all perfect, a pronunciation problem probably doesn’t come alone. It makes sense to try to minimise the number of errors, including in pronunciation.

Naturally, given context, the listener might still be able to understand what you’re saying, but what I’m trying to get at here is that if you burden the listener with enough problems like this, they will have a harder time understand what you’re saying. You can of course be understood with a heavy accent in a language, but usually only after the listener has become used to the way you speak or if they’re familiar with your kind of accent from previous experience.

Clear pronunciation is easier to understand and makes it easier for people to talk to you

For communication to work properly, we need to make sure that the sounds we produce in Chinese are correctly categorised by native speakers, but we don’t need to sound exactly like native speakers to be clearly understood.

To use a slightly more technical language, we could say that our speech needs to be good enough to lead to phonemically accurate judgements by native speakers, but we don’t need perfect phonetic accuracy.

What does this mean in practice? It means that it’s fine if your pronunciation of Chinese initials, finals and tones is a bit off (which will leave you with a noticeable accent), but it’s not okay if they’re off by enough to make it hard for native speakers to correctly process the sounds. If you want to say jiā but it comes out somewhere between jiā and zhā, you have a problem and you need to fix it. If you just say jiā with an initial that is a bit odd, that’s not necessarily a big problem.

Ideally, your pronunciation should be good enough for native speakers to understand you effortlessly, meaning that they don’t have to struggle to understand you because of the mistakes you make. This can sometimes be hard to judge, because a teacher who has listened to your pronunciation for a while will have a much easier time understanding you than a complete stranger, which explains why the real world sometimes can feel very unforgiving.

Reason #2: Pronunciation is a representation of you and your Chinese ability in general

Apart from the fact that we don’t want to put to heavy a burden on the listener, the second reason that pronunciation matters is that it partly determines how other people regard you and your Chinese ability. To be judged like this is grossly unfair, but it’s still true and something we probably want to consider as second language learners.

Let me explain. The reason speaking (of which pronunciation is an important part) is so important is that most other language skills are mediated through speech, at least in everyday life and in real-life interaction. You might consider Tang poems as light reading for breakfast, but if you can’t talk about them in Chinese, people aren’t going to be very impressed. I can say that I have studied Chinese for so and so long, learnt so and so many thousand characters, and that I have read several hundred books in Chinese, but it’s still hard to believe if I pronounce Chinese with a heavy accent, rife with errors. To prove passive skills like reading and listening, you almost need a standardised test, which is rather abstract and might be meaningless to outsiders.

Pronunciation is not like the other skills. It strikes the listener directly in the face (the ears, to be more precise). How good your pronunciation is in general can be judged very quickly and an opinion is formed automatically by anyone who hears you, not just professionals who work with pronunciation. I’ve become used to analysing and diagnosing students’ pronunciation over the years because of courses I teach at university and the pronunciation course I offer here on Hacking Chinese, but what I’m saying is that even normal people will automatically form an opinion of your pronunciation almost immediately, even if they might not be able to explain how they came to that opinion.

I guess this is similar to writing (and handwriting) at least back in the days before computers were used. It’s simply hard to believe that someone who writes like a five-year-old is an expert in another area of Chinese. It might of course be true, it’s just harder to believe it compared to if that person wrote at a comparable level.

We judge books by their covers all the time, even if we know we shouldn’t

We all know that we shouldn’t, but we still judge people based on superficial factors, unconsciously, all the time. I think people in general tend to underestimate people who have bad pronunciation and overestimate people who have good pronunciation.

This is not limited to pronunciation either, but can be expanded to language proficiency in general, of which pronunciation is just a particularly noticeable part. For instance, take a few moments to think about immigrants you have met in your own country who speak an accented version of your native language. Even though we don’t want to, it’s very easy to think that foreigners with good pronunciation are “better” than those that have poor pronunciation, including in areas which aren’t related to speaking or even to languages at all.

While it’s outside the scope of this article, there’s certainly much prejudice towards immigrants in general because of language ability, even in areas where language ought not be very important.

Reason #3 (bonus): Good pronunciation helps you win the language struggle

Scott Burgan pointed out to me on Facebook that there is another advantage of having good pronunciation, namely that it helps you win the language struggle. A single sentence pronounced well and at a natural pace will convince most people that they can converse with you only in Chinese instead of insisting on English.

This is much harder (next to impossible sometimes) with good grammar, vocabulary, reading/listening and so on. Of course, this might also lead to the infamous binary judgement of foreigners’ language proficiency: “Either you know nothing or you are near-native”, so if your pronunciation is better than your overall ability, be prepared to ask people to repeat themselves and/or slow down!

Reason #4 (bonus): Improving your pronunciation can help your listening ability

Julien Leyre, among others, pointed out in the comments that there is a phenomenon where improving one’s pronunciation will lead to improved listening ability, which is something I have experienced and observed myself. The likely reason for this is that attention matters greatly in language learning, so by properly learning how something is pronounced, you will then also be able to pay attention to the right cues when other people speak with you.

There is some research to suggest that pronunciation practice can improve your listening ability, but it’s notoriously difficult to sort out what factors influence which here, because it’s also certainly true that listening practice influences your pronunciation, which is why I stress listening so much in my course, and generally advise students who struggle with pronunciation to listen more in tandem with studying pronunciation.

Pronunciation matters more than you think

So, pronunciation does matter and it matters regardless if you like it or not. Bad pronunciation puts a higher load on the listener, which combined with other errors, can make it difficult or tiring to talk to you. And you might know that your Chinese is awesome, but if pronunciation is the weakest of your skills, it’s bound to have a big impact on how you are perceived by others. Since this can be important both in a private, social situation and in a professional or business situation, focusing more on pronunciation is usually a good idea.

Of course, it’s a matter of priority, so I’m not saying that pronunciation matters more than anything else, I’m just saying that it matters throughout your Chinese studies, up to an advanced level, not just at the beginning. It’n to easy to reach a level where you can fool native speakers into believing that you’re also a native speaker, but that’s no excuse for making basic mistakes with tones, initials or finals. Simply put, people stop caring about pronunciation too early rather than too late.

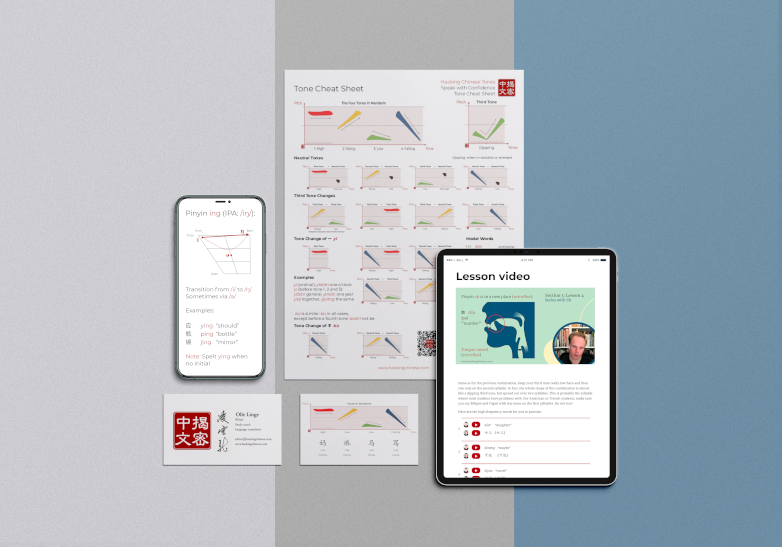

If you want to improve your pronunciation and make sure you can communicate clearly in Chinese, regardless if you’ve been learning for a week or a decade, Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence. If it’s not available when you read this, you’ll be given the chance to leave your email address so I can notify you when the course becomes available again!

10 comments

Great post, as always!

I wanted to add something – actually, a personal observation I’d like to test. I’ve observed a correlation in myself and some of my students between pronunciation and listening ability. Basically, through some sort of odd muscular mapping influencing parts of the cortex or ear tuning or whatever, when I make some sort of ‘aha’ progress in pronunciation, whether it’s rhythm, consonant clusters or vocalic distinction, I also start understanding better, basically by better hearing what people say. I’m unsure if there’s research on that, and whether it’s an oddity of my brain or a general trait, but I’d love to hear if anyone else (or you Olle) have observed this.

Also, I’ve just published a post today on my blog about three areas of Chinese pronunciation where I’ve noted significant progress after changing some ‘odd’ element – softening consonants, using my diaphragm, and making my vowels more nasal. I would also love to test these! The post is here: http://julienleyre.wordpress.com/2014/02/20/three-core-tips-on-pronouncing-chinese-2/ – I’m basically trying to address the core problem of ‘how to sound more Chinese’.

Interesting! Are you referring to some other language than Chinese? There aren’t that many consonant clusters in Chinese… Anyway, I think the normal thing is for perception to improve production rather than the other way around, but I suppose the opposite is possible. For instance, once you realise how something is pronounced, it might be a trigger that suddenly allows you to notice something you didn’t notice before. This happens with vocabulary all the time. You hear a word for the first time (you think), learn it and suddenly hear it everywhere! This is of course not because other people suddenly start using the word, they did that all along, you just didn’t pay attention. I’ve had this experience more times than I can count and I think it’s a general phenomenon of noticing.

I’ve had this happen to me both in Chinese and other languages. Indeed, this works like vocabulary recognition – at a sort of ‘meta-level’.

Thanks for the recognition Olle, 😉

I can’t remember where but I have definitely heard of what Julien Leyre is saying about being able to pronounce a sound (and distinguish between close sounds) and then this enhancing listening comprehension in academic ESL literature somewhere. Although I can’t remember where though, so not really much help I’m afraid!

If you can’t say it properly, you likely can’t hear it properly as well. Returning to review of pronunciation for some period on an annual basis is a very good thing.

As you progess, you will enjoy confidence in sounding more and more like a native speaker.

Indeed true, I have often had a very positive response from a simple well pronounced 你好,leading to an overestimation of my overall level.

I found a lot of new learners of Chinese in Taiwan like to talk fast when in doubt about their pronunciation and hope that the listen will pick up the meaning from the context.

This is a rather negligent habit of loading the other person with more than their fair share of the communication burden.

On the other hand, you do run into fast talkers that you just can’t sort out. Often they presume your level is higher than it is. It is very remarkable how just asking them to slow down often results in them using less presumptive idiom and the whole conversation becomes coherent.

This is a very natural part of negotiation of communication. It really doesn’t matter which language it is, just asking people to slow down tends to shift to a simpler vocabulary and more verification of understanding.

Be sure to ask for such if you are having trouble keeping up.