It’s safe to say that pronunciation is an overlooked area of learning Chinese. Typically, pronunciation is covered in the first few weeks or sometimes just the first few days of a beginner course. After that, what happens depends on how quickly students learn the tones, initials and finals. And the teacher, of course.

It’s safe to say that pronunciation is an overlooked area of learning Chinese. Typically, pronunciation is covered in the first few weeks or sometimes just the first few days of a beginner course. After that, what happens depends on how quickly students learn the tones, initials and finals. And the teacher, of course.

Students who are good at mimicking and learn quickly are often ignored (because they are already doing better than average).

Students who are slower to learn are often ignored too after a while (because the teacher gives up or doesn’t have time for them). What remains is sporadic feedback for the students in the middle.

Two types of beginner pronunciation problems

In this article, I’m not going to talk about specific problems with pronunciation, but rather two entirely different types of problems. These often become mixed up, not only by students, but sometimes also by teachers. This makes it significantly harder to learn pronunciation, so my goal here is to make sure you know the difference and what to do in each case.

Here are the two problems put briefly:

- Not being able to produce the correct sound – This is the type of problem that most people will think of when they think of problems with pronunciation. You already know that this is not the only type because of the title and introduction of this article, but many people act as if they believe that this is the only type of pronunciation problem. An example would be the sound that in Pinyin is written ü, which is actually not that hard to pronounce, but causes some problems for native speakers of English since there is no similar sound in that language (but there is in French, German and Swedish, for example).

- Not being able to correctly link the spoken sound with the written form of that sound – This means either not being able spell the correct sound using Pinyin (in a listening test) or not being able to recall which sound in the spoken language is associated with a certain Pinyin spelling (in a speaking test). Of course, never having learnt how Pinyin works would be an even bigger problems, since it’s impossible to recall something you haven’t learnt.

Since the first type of problem is what most other resources focusing on pronunciation deal with, I will not discuss it further here. There is no simple, blanket solution to learn to pronounce new sounds correctly, but I suggest you start by listening closely and then mimicking as much as you can.

Even though I have no empiric data to back this up and base this only on my own experience teaching beginners, not being able to connect sound and written symbols actually causes more bad pronunciation for beginners than the tricky sounds do, at least for beginners.

Learning spoken sounds through written symbols

The problem of linking spoken sounds and written symbols is often the result of somewhat artificial classroom or online learning. What I mean is that if all language learning happened in natural conversations with native speakers, we wouldn’t have students who think that the u in xu and the u in shu represent the same sound. This is very obvious if you only listen to the spoken language (in fact, you’d have no reason to think they are the same), but impossible to know if you’re not familiar with Pinyin orthography (since they do look identical).

Thus, in an ideal world, students would have the time and resources to learn pronunciation without written support, relying on spoken language only, and only then learn how to write the sounds.

However, that is impractical as you can not take notes, search for resources online and will have to rely heavily on help from a real human, which is going to be very expensive. Few resources are easy and convenient to use in audio-only mode.

So, we’re stuck with students learning pronunciation and Pinyin at the same time. This has both good and bad, depending on how you look at it:

- It’s good because it offers a shortcut to writing the sounds in Mandarin. Many sounds are written with symbols that represent the same sounds in English (e.g. l, m, f) or are at least similar (e.g. p, t, k). This makes it easier to get started and has other advantages, such as quicker typing and less time spent on learning extra symbols.

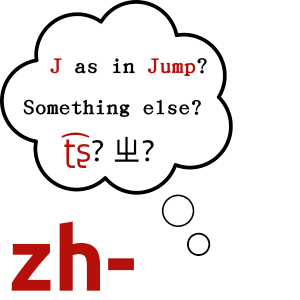

- It’s bad because there are many sound representations that aren’t pronounced anywhere near how they are pronounced in English (e.g. j, z, c) or simply don’t exist in English (e.g. x, zh, -ü). This means that students will guess incorrectly in the first case and be left to make something up in the second case.

While there are other solutions available to write down the sounds in Mandarin, such as Zhuyin and IPA, these have their own set of drawbacks. If you want to read more about those, please check out the article series starting with this post:

Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

Figuring out which type of problem you have

Both teachers and students need to be aware of the risk of mixing up the two types of pronunciation problems we’re talking about here, i.e. not knowing how to produce the correct sound and not knowing how it’s written.

As a student, always start by mimicking, preferably a teacher or native speaker who can give you feedback. That ensures that you know how to pronounce the sound. Mimicking makes sure you’re not influenced too much by how something is written, which can cause a lot of trouble in the beginning. You should also invest the time to really learn Pinyin well, otherwise you won’t know where you went wrong.

As a teacher, it’s equally important to realise that there are at least two things that can lead to (the same) incorrect pronunciation. You need to know if the student pronounce the u in xu the same as the u in shu because she doesn’t know that they aren’t the same and just assumes they are because they are written the same, or if she really can’t pronounce the ü sound! In the first case, you need to teach how Pinyin works, in the second case, you need mimicking or an explanation/demonstration of how to produce the correct sound.

Two different problems; two different solutions.

Whatever transcription you use, learn it and learn it well

None of the commonly used systems for writing the sounds of Mandarin is terribly complicated. You can easily learn all the spelling rules, exceptions and other peculiarities of each system in a handfull of hours of active studying (preferably spread out over time, so not just when you first start learning). Naturally, it takes longer than that to learn how to nail each sound in every situation, but that’s another type of problem, remember?

Don’t think that you will naturally absorb all these rules without investing some time into studying them directly. There are perhaps some people who can do that, but I’m not among them, and the average student I teach certainly can’t do it. That’s why I sometimes encounter students who have studied for years and are still surprised by some of the things mentioned in the article linked to below.

If you use Pinyin, don’t think you know how something is pronounced just because the letters are familiar to you.

Instead, you should study each and every initial and final, making sure you know how they sound and how they are spelt. Sometimes, this is easy, such as la or ma, but sometimes, the correct pronunciation is not even close to what you’d guess, such as shi or que.

To help you along, I suggest you check out the following articles:

- A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learn Mandarin pronunciation

- Focus on initials and finals, not Pinyin spelling

Whatever the underlying cause, it’s still wrong

In this article, I’ve explained why it’s important to know why your pronunciation is wrong and not just that it is wrong. This is because different root causes have different remedies, so practising tongue positions has no effect on your ability to spell, and studying spelling rules have marginal effect on your ability to produce different sounds.

That being said, the end result sounds the same and has the same kind of impact on your ability to communicate in Mandarin. Every incorrect sound makes it harder for other people to understand what you’re saying.

While I understand that spelling is not very interesting to study for most people, it really is important if you learn Chinese mostly through written symbols and letters, as most of us do these days. I don’t mean that it matter if you capitalise Pinyin correctly or put the tone mark over the correct vowel, I mean that you know how the sounds are written.

Being able to produce the sounds themselves is of course the real challenge and where you will spend most of your time, but not learning simple spelling rules will also impact your ability to communicate.

Conclusion

So, learn how the sounds are written, and how the written sounds are pronounced. Studying all of this once at the beginning of your first semester will not cut it. It’s likely teachers will not teach Pinyin in upper beginner and lower intermediate courses, so you might need to do this on your own. This is perhaps the most egregious shortcoming of how Mandarin is taught.

Assuming that there is only one cause of pronunciation errors will lead to a lot of frustration and wasted effort. Figure out what the problem is… and fix it!

2 comments

What I’ve almost never seen done is teaching students the correct mouth movements for sounds. Mimicking is just assumed to be the answer. Well you can’t mimic a sound that requires a strange mouth movement that you’ve never considered using. How’s a student supposed to figure out X or Q on his own?

That’s a good point. The reason I don’t write about it much (although it is covered in the beginner course) is because it’s very resource intensive and I simple don’t have the know-how and money/skills to produce accurate and instructive graphics/video for something like this. I do show/talk about this in class when teaching all the time, though. That’s quite rare, though, I’m somewhat of a phonetics nerd after all. The truth is that most teachers, native and non-native alike, simply don’t know enough phonetics to accurately describe (draw, explain, whatever) all the sounds. So, it’s either because it’s hard/expensive/time-consuming to produce or because the teacher doesn’t know enough to do it. Or both!