Spaced repetition software is one of the most powerful tools available for language learners. While you obviously don’t have to use spaced repetition software to learn Chinese, it’s probably the most efficient way of learning vocabulary, so it makes sense to give it a serious try.

Spaced repetition software is one of the most powerful tools available for language learners. While you obviously don’t have to use spaced repetition software to learn Chinese, it’s probably the most efficient way of learning vocabulary, so it makes sense to give it a serious try.

Having spent well above a thousand hours using various systems over the years myself, I think I qualify as having given it a serious try. And before you leave a comment saying that a thousand hours is crazy, it actually only averages out to about 15 minutes per day since I started learning Chinese. The point is that I’m still using spaced repetition software today (let’s call it SRS from now on) .

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

In this article, I want to look closer at one of the dilemmas with SRS. It turns out that one of the main strengths of SRS is also its biggest weakness. SRS is really good at some things, but you can’t apply it to everything and expect the same result.

If you haven’t tried any SRS for learning Chinese, I recommend the following:

- Anki (for the tinkerer, free)

- Pleco (integrated with the best dictionary app, single purchase)

- Skritter (best for Chinese characters, subscription)

The basics of spaced repetition software

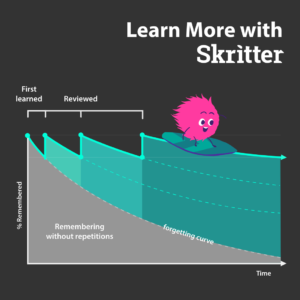

I’m not going to go into details here, but to make sure we’re on the same page, when I say SRS, I’m talking about computer programs that schedule flashcard reviews based on a certain algorithm to increase memory retrieval. The underlying principles are those of active recall (you’re not just seeing or hearing the word, but actively asked to retrieve it from memory) and the spacing effect (reviews spread out over time leads to higher chance of retrieval later, compared to reviews clumped together).

You don’t have to use spaced repetition software to benefit from either of these principles. You can create flashcards on paper and you can create your own review schedule (such as a Leitner system). You can also rely on large amounts of listening and reading to create a natural kind of spaced repetition, which also includes active recall to a certain extent. The same goes for engaging in spoken and written conversations. I’ve written more about spaced repetition here:

Reviewing just when you’re about to forget

Spacing your reviews and relying on active recall is almost always good. I’m not going to argue that you should start clumping your reviews together or reread your textbook as a means of remembering how to write the characters in it, because it won’t work.

Instead, I will highlight a problem with the goal of the scheduling behind most of these programs and your goals for learning Chinese. Correct scheduling can lead to huge gains in efficiency (defined as items kept in long-term memory per unit time spent reviewing) by relying on longer and longer intervals between reviews. The better you know something, the longer you can wait before you risk forgetting it.

Picture a black hole of forgetfulness.

Every time you review something, you throw it up in the air, away from the hole. Then, the black hole gradually sucks it back down again, and unless you review the item again, it will be swallowed up and forgotten. For each time you do review, though, the item gets hurled farther away from the black hole, taking longer to fall into oblivion.

Every time you review something, you throw it up in the air, away from the hole. Then, the black hole gradually sucks it back down again, and unless you review the item again, it will be swallowed up and forgotten. For each time you do review, though, the item gets hurled farther away from the black hole, taking longer to fall into oblivion.

This is an appealing analogy and works extremely well for some types of learning. For example, if you want to learn the capitals of all the countries in the world, all the chemical elements, or the muscles and bones of the human body, using SRS is extremely good. If used in a disciplined manner (i.e. regularly), you can maintain knowledge of these things without spending much time per item, much less than you would using any other type of reviewing.

Learning Chinese is not like learning geography

But learning a language is not like learning to label things in geography, chemistry or anatomy. A language is structured system for communication. To be able to communicate, you need to truly master basic vocabulary and grammar; just barely recalling what something means is not enough. When it comes to the core few thousands of words in a language, you need to know them immediately and intimately to be able to use the language well.

To show how much you can actually do with just a thousand words, I wrote an article here on Hacking Chinese using only the thousand most common words in English, and many readers didn’t even notice! To do that, you need to really, really know the words well. When it comes to the spoken language, you also need a certain amount of speed to achieve fluency; if you stop and think about every word, you will not be able to have a conversation.

To show how much you can actually do with just a thousand words, I wrote an article here on Hacking Chinese using only the thousand most common words in English, and many readers didn’t even notice! To do that, you need to really, really know the words well. When it comes to the spoken language, you also need a certain amount of speed to achieve fluency; if you stop and think about every word, you will not be able to have a conversation.

When spaced repetition fails…

The algorithms that underlie most of the spaced repetition systems today are often based on one of the algorithms from SuperMemo, which aim for long-term retention which as much efficiency as possible. They are optimised to allow you to give the right answer to a flashcard review months and years from now.

They are not optimised for teaching you how to recall the meaning of a spoken word in half a second, rather than two seconds, which might be the difference between being able to keep up with a conversation and falling hopelessly behind (read more about this problem in my article about listening speed).

While you can in theory use SRS to build both speed and depth of knowledge, it doesn’t always make sense to do so, and most commercial SRS are not built for this. The original algorithm is actually based on grading reviews on a scale from 0 to 5, where five indicates perfect response with no hesitation, and 0 represents a complete blank. However, you can still reach very long intervals with this method by achieving 3-4 on most reviews (“correct response recalled with serious difficulty” and “correct response after a hesitation” respectively).

A basic principle of SRS is to break down each flashcard into as small units as possible, but in this direction madness lies. You can’t add a card for everything, especially not for Chinese where each basic character has three pieces of information (writing, sound and meaning), rather than the two pieces most other languages have. You’ll drown in flashcards.

A basic principle of SRS is to break down each flashcard into as small units as possible, but in this direction madness lies. You can’t add a card for everything, especially not for Chinese where each basic character has three pieces of information (writing, sound and meaning), rather than the two pieces most other languages have. You’ll drown in flashcards.

When it comes to speed, you could grade yourself very harshly. Let’s say you hear the word kuàisù. You would then only grade yourself as being correct if you associated it with the meaning “fast” if you did so without hesitation.

…and what to do about it

I said in the introduction that I still use SRS regularly, because while no method or tool can be optimised for everything at once, there are still many situations where using SRS makes sense. Here are a few reasons why I think SRS is an essential tool for Chinese learners:

- Slow recall is better than no recall – While it’s obvious that barely being able to recall common words won’t cut it, being able to recall a word is much better than not being able to recall it. This means that SRS can serve as a stepping stone to more reading and listening. You will not build the speed and depth of knowledge you need just by doing flashcards, but you will improve your ability to make sense of written and spoken Chinese, which in turn allows you to consume more Chinese, which will increase your speed and depth of knowledge.

- Speed is not always necessary – In many situations, speed is not a big factor, especially not for characters and words on the limit of your proficiency level. As a beginner, you really need to know your pronouns, basic verbs and nouns, but it’s okay if you struggle with rarer ones, and stopping for a few seconds to recall something is not really an issue, as long as you don’t do it for every word. As your Chinese improves, the range you need to know quickly increases, of course. Written skills are also less sensitive to speed, at least in the real world. You can just take your time reading a text in Chinese or writing something by hand (unless you take an exam or similar); speed is not necessarily that important.

- Superficial recall is better than no recall – Your goal when using SRS to learn a language is not to use it to master every aspect of every word. Instead, the main goal should be to recall the basic meaning, or even just something at all about the word. That is certainly better than not remembering anything at all. In this way, SRS again serves as a stepping stone to more reading and listening.

- Deep knowledge is not always a requirement – If you’re going to write an article like I did above with only 1,000 words, you really need to know those words, but most of the time, simply knowing the gist is enough. For example, when reading, knowing roughly what the individual characters in a word mean might be enough for you to guess the full meaning in context. SRS is very good at helping you recall the basic meaning of characters and words, enough so that you can then make more sense of the Chinese you read and listen to, which will in turn give you the depth you need.

So, spaced repetition software is still one of the most powerful tools for learning foreign language vocabulary, it’s just not the only thing you should be doing. It’s a tool among many in your learning toolkit. You can use it occasionally to deal with problems of both speed and depth, but I think large amounts of listening and reading is better for this. See my article about extensive reading for more about this (the same can be applied to listening, of course):

Build both speed and depth by reading and listening more

The best way to improve reading speed is to read more. The utility of fast recall is proportional to how frequent the item in question is, so it’s much more beneficial to be really fast when recalling 的, 一, 不, 是, and 了 (the five most common Chinese characters) compared to 嗓, 蹲, 焚, 淘 and 嫩 (the five least common characters among the top 2,500).

Since you are, on average, more than 500 times likely to see the first set than the second set, you will of course build speed for these characters more quickly. You vill also see them in various contexts and combinations, deepening your knowledge of how they are used.

The same goes for listening, of course. The more you listen, the more you will hear the most common words. After a while, you will know them so well you don’t need tot hink about what they mean any more.

You will of course still encounter words you don’t know, but that’s okay. Taking a second or two to recall a specific word in a sentence is fine, you just can’t do that for every word. Even if you don’t know the word at all, your knowledge of the rest of the sentence might give you some clues or at least allow you to keep listening without losing track completely of what’s going on. This is an area I think SRS is underused, since many traditionally think of flashcards as being visual. Of course, with digital flashcards, you can have only audio on the front, which is easy to set up in Anki:

Free and easy audio flashcards for Chinese dictation practice with Anki

As you learn more, your requirements also change

Naturally, what constitutes your core vocabulary will vary. As a beginner, you don’t need to be able to recall the name of a country, even a well-known one, very quickly unless it’s the country you’re from or China. However, if you as an advanced learner need to stop and think about what 德國 means, you have a problem.

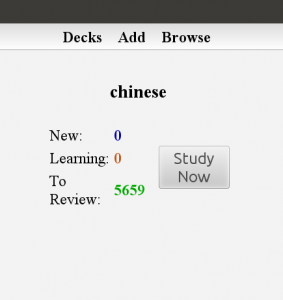

This means that the more you learn, the less you will need the flashcards you added earlier. This is not a problem, though, because if you review regularly, these easy words will have so long intervals that reviewing 你好 once every ten years doesn’t really matter. There’s no need to nuke your flashcard deck and start from scratch, and keeping the words in there is good as a safety check, as well as for future reference (it’s very easy to tell people what you know and don’t know, for example).

However, this is also the reason that doing exactly that, i.e. deleting everything and starting from scratch, is actually not as crazy as you might think at first, especially if you’ve fallen behind a lot as an intermediate or advanced learner. It makes little sense to spend weeks ploughing through thousands of flashcards you know very well. Better then to start from scratch, and add words in the range where SRS really shines.

Conclusion

The biggest advantage of SRS is the optimised intervals that serve you reviews just before you were about to forget. This, however, is also its weakness when it comes to language learning, because it’s often the case that just being able to recall something is not good enough.

As we have seen, though, this problem is not as serious as it looks at first, because if you pair SRS with large amounts of natural listening and reading, the problem mostly goes away, and you can reap the benefits of using both SRS and extensive reading and listening!

2 comments

I think SRS mainly becomes a problem when you expect it to substitute for actually speaking, reading, listening, etc.. If you treat it as a way to augment your normal vocabulary acquisition, however, it’s fantastic.

The core vocabulary used in speaking/listening really does need to be practiced directly.

Yes, agreed. I actually wrote about that a few years ago, but forgot to link to the article this time around (you can check it out here: If you think spaced repetition software is a panacea you are wrong. It’s always tricky to write articles like this, because for people who have a balanced approach or don’t really know what SRS is, the primary goal should be to make them try it out, whereas the real question I want to discuss is relates more to how we use SRS, mainly for what, along with some criticism that are often brought up (such as it not being suitable for languages at all, which is a bit odd in my opinion).