This article about wuxia is written by Sara K.. After reading this article, I wanted to read more wuxia, and I hope that you will too! Of course, even if the focus this month is on reading, don’t forget that wuxia isn’t limited to books and comics!

This post is split into five parts:

- What is wuxia?

- Wuxia in Chinese-speaking society

- Why is wuxia relevant to Chinese learners?

- Some notes on the language in wuxia

- How to get started with wuxia

Short answer: Chinese martial arts fiction featuring heroism, usually set in imperial China.

Long answer: A few wuxia movies, such as Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon and Hero, are famous in the English-speaking world. While I don’t think these movies are the most representative of the genre, they are genuine wuxia, and anyone who has seen them already has some idea of what wuxia is.

Sometimes, I see ‘wuxia’ translated into English as ‘tales of chivalry’. Wuxia stories are not ‘tales of chivalry’. ‘Chivalry’ is based on a medieval European code of conduct for knights, who were almost always of noble lineage, and was about maintaining the feudal system. Most wuxia heroes come from the peasant class, and would not mind taking the aristocracy down a notch. The ‘xia’ in ‘wuxia’ does not mean ‘chivalry’, it means standing up for what is right. To give you a sense of what ‘xia’ really means, note that Batman’s Chinese name is 蝙蝠俠(‘The Bat Xia’) and that Spiderman’s Chinese name is 蜘蛛俠 (‘The Spider Xia’). Comic book superheroes are much closer than Sir Lancelot to being wuxia. Just because many wuxia stories are set in medieval China does not mean they are the equivalent of tales set in medieval Europe.

If one must find an equivalent in medieval Europe, the obvious one is Robin Hood, though I’d like to note that in Robin Hood, King Richard is usually depicted as a good guy, whereas in wuxia fiction, the emperor of China is generally, at best, a neutral party or a very grey character.

Over at Yago, I compared wuxia to Star Wars, mainly because it’s a good way to explain what wuxia is in few words. However, I think the best equivalent to wuxia in the English-speaking world is the Western genre. In fact, some Americans even call wuxia stories ‘Easterns’ The similarities include:

- A historical setting

- The government is corrupt or otherwise non-functional, so common people have to take care of justice themselves

- Frequent use of gorgeous natural scenery

- Interaction among different ethnic groups, including a dominant nation (China/United States) whose boundaries are constantly shifting, tribal nations (Khitans, Miao, Uyghurs, Navajo, Lakota, Cheyenne, etc.) and characters from other nations (Korea, Portugal, India, France, Mexico, Russia, etc.)

- The focus is generally on personal vendettas and debts of gratitude, not trying to save the world

- Being strongly tied to a specific culture/country. Though there are spaghetti Westerns and wuxia books/comics/TV shows from southeast Asia, Westerns are almost always strongly tied to the United States, and wuxia stories are almost always strongly tied to China. Other genres, such as science fiction and romance, are not married to a particular culture/country.

However, any comparison between wuxia and non-Chinese fiction must be limited, because wuxia arose in the Chinese-speaking world, and it could have arisen nowhere else. Wuxia rides on Chinese-speakers’ history, ethics, medicine, ecology, philosophy, hopes, dreams, and nightmares.

For more description, head over to TVTropes (though note that I do not agree with everything said there).

Wuxia in Chinese-speaking society

While there is debate about when/how the wuxia genre emerged, most people would say that it reached maturity in Republican China in the 1920s and 30s, when it was the most popular genre of Chinese fiction. Wuxia was part of the national conversation about how to be Chinese in the modern age. For example, a prominent 1920s’ writer, Xiang Kairan, was also involved in promoting traditional Chinese martial arts and incorporating ideas from science and European athletics. I think this period of Chinese history left a powerful mark on wuxia, even decades later, in both the openness to new ideas, and the cynical outlook.

Of course, as with any popular genre of fiction, there have been people saying that it is bad influence: it’s too violent, it’s anti-Confucian, it’s just for juveniles, etc. As a non-Chinese person, I don’t completely get the stigma of wuxia, but then again, popular genres such as science-fiction, romance, and YA get stigmatized outside of the Chinese speaking world.

Even after the People’s Republic of China banned wuxia, and the Republic of China (Taiwan) put it under heavy censorship, wuxia continued to be wildly popular – if anything, government censorship made wuxia even more appealing. Where wuxia writers had the freedom to do so (Hong Kong), they sometimes used wuxia as a platform to criticize politics and society.

Though wuxia TV shows and movies continue to be very popular, wuxia novels (from which most TV shows and movies are adapted) supposedly went into decline in the 1980s. What this really means is that, instead of being a mainstream genre, it became a thing mainly for geeks (though mainstream readers are generally still familiar with the ‘classic’ wuxia novels).

Why is wuxia relevant to Chinese learners?

Here is one reason: wuxia is so deeply woven into Chinese-speaking culture that at times you won’t understand what people are saying without some familiarity.

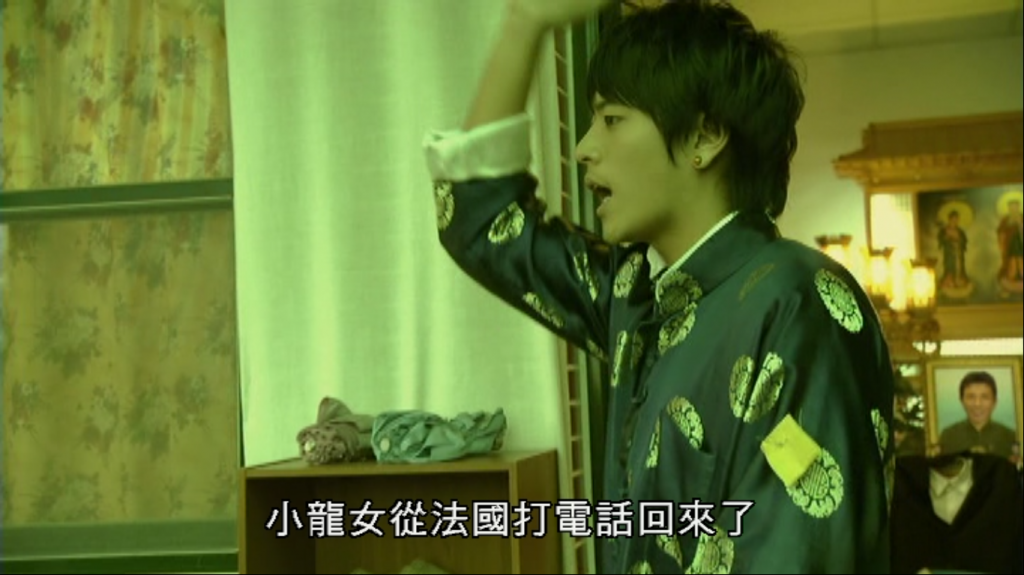

Here is an example; in the movie Seven Days of Heaven, which is a Taiwanese movie set in contemporary Hong Kong and Changhua, a character at one point says 「小龍女從法國打電話回來了」 which roughly means “Xiaolongnü is calling from France”.

Most adult Chinese learners would wonder what ‘Xiaolongnü’ means. However, most native Chinese speakers over the age of 10 know exactly who Xiaolongnü is: she’s a is a mysterious beauty and dangerous sword fighter who grew up in the Tomb of Living Death (活死人墓). In addition to fighting with swords, she can use poison gold needles, and attack people with the sashes of her sleeves. In spite of her chronological age, she always looks like she’s sixteen years old – it’s implied that her body does not age because she’s not entirely alive. She’s like Sleeping Beauty, except she’s not asleep and is a dangerous martial artist.

A big poster depicting Xiaolongnü across the street from Taipei Train Station. Generally, if you see a beautiful maiden wearing a white dress who looks like she’s from pre-modern China, you’re probably looking at Xiaolongnü.

So why is this movie dropping a reference to Xiaolongnü? It’s more poignant (and succinct!) to say ‘Xiaolongnü’ than to say ‘the person who is so much at the center of your existence that you wouldn’t want to live without her, yet she is beyond your reach’.

When I read in English “I thought mentioning [something] was just like saying ‘Voldemort’”, I understand it because I’m familiar with the plot of Harry Potter. The most popular wuxia stories have also reached the stage where Chinese speakers will drop references to them and expect to be understood.

Name-dropping manifests something deeper: wuxia is an integral part of Chinese-speaking culture. You will probably never encounter enough name-drops to justify learning about wuxia for that reason alone … but wuxia is thoroughly Chinese in a way that no other genre of fiction is, which makes it an excellent vehicle for getting into the minds of Chinese-speakers.

I have learned a great deal about the subtler nuances of the Chinese language by reading lots of wuxia, some of which I don’t think I could have picked up by reading literature-in-translation.

Wuxia offers many paths to get to know Chinese culture better – for example, I can look up the various places mentioned in the novels and improve my understanding of Chinese geography, I can look up the herbs used and learn something about Chinese traditional medicine and botany (that’s how I learned about a very cool plant called ‘gastrodia‘), I can look up the actors who play Characters Y and Z, and see what other TV shows/movies they acted in… and so forth. Of course, I ignore all this most of the time I do because there are only so many hours in a day, but I think that because wuxia connects to so many aspects of Chinese culture and society, it is an excellent node for one’s knowledge web.

Then there is the way that being familiar with wuxia changes my relationship with native Chinese speakers. When I reveal that, yes, I have also read [famous wuxia novel], it cuts down the mental distance between us. Some native Chinese speakers think this is wonderful, others are not comfortable with the fact that I’ve shared that part of their head space, but it always makes me less of an outsider.

However, by far the most important benefit wuxia has for me is that it makes me much more motivated to study Chinese. I think the above reasons are enough for all Chinese learners to at least learn about wuxia, but I think the possibility of turning into a wuxia fan is the biggest reward. If you turn into a wuxia fan – as I did – you suddenly have enough material that you’re motivated to read/watch to keep you going for a long, long time, and since very little of it is available outside of Chinese/Vietnamese/Thai/Indonesian/etc., you have to read/watch it in Chinese (unless you understand one of those other Asian languages).

Not everyone loves wuxia, and if reading/watching a couple stories fails to pique your interest, then drop it. But if you don’t try, you can’t know whether or not wuxia suits your tastes.

Some notes on the language in wuxia

I should also note that the Chinese in an wuxia novel is going to be a bit different from, say, contemporary conversational Mandarin, just as the language in a Tolkien novel is a bit different from what you’ll hear in a California high school. For example, just this morning I was watching a TV show, and I repeatedly heard ‘他圓寂了’. That a literary way of saying ‘he’s dead’. Reading/hearing the much plainer'他死了' is also common in wuxia (in fact, it’s more common than ‘他圓寂了’), but it’s still an example of how the language can be different.

I learned the language simply by reading, looking up stuff I didn’t understand, and putting the new expressions into my SRS. However, it might be a good idea to learn many different ways of saying ‘die/kill’ in Chinese, because it’s generally important when a character dies. I think learning other specialized vocabulary is generally not necessary to understand the story (and if it is necessary, it will probably get repeated a lot).

Here’s a list of terms which mean ‘die’ or ‘kill’ which I’ve extracted from wuxia novels:

Editor’s note: I have added links to the relevant entries on youdao.com.

(Notice the pattern in the above three words)

(Notice the pattern in the above two words?)

(Notice the pattern in the above two words?)

(Notice the pattern in the above six characters/words?)

Not all of these terms mean the same thing (for example, some only apply to young people who die, and some only apply to old people who die) so you should look at the dictionary entries. Of course, the best way to learn these terms is to see them in context.

Classical Chinese has a way of sneaking into wuxia, and occasionally there’s even entire poems written in Classical Chinese. I have an easy technique for dealing with classical poetry – ignore it. It’s never interfered with my enjoyment of the novels. As far as Classical Chinese words being mixed with Mandarin – you can learn it like you would learn other unfamiliar vocabulary, or you can ignore it.

Finally, the language difficulty runs the whole range from novels which consist mostly of simple short sentences to works full of sophisticated wordplay. Obviously, the former is a much better place to start.

How to get started with wuxia?

‘How to start’ depends on your level of Chinese, but first, an exercise that is suitable for learners at all levels:

Ask native speakers about wuxia

- Find a native speaker to talk to.

- Ask them which wuxia stories they have read/seen.

- Ask their opinion about those stories (for example, if you are a beginner, you can ask questions like 你喜歡嗎?)

- Ask them to describe an wuxia story to you.

- Repeat with another native speaker.

After doing this exercise with a few native speakers, you’ll have a pretty good idea which wuxia stories tend to be sources for name-drops…

For beginning learners

No, you cannot read a wuxia novel or watch an wuxia movie without subtitles, at least not yet … but you can still learn about wuxia. There are some online English-language resources about wuxia:

- Chinese Culture Wuxia Web, hosted by the Taiwanese government

- Wuxia Wikia (currently very incomplete)

- Wuxiapedia, hasn’t been updated in years, but still informative

- A desciprion of a wuxia fight scene written by… me

You will learn something about Chinese-speaking culture, and it might motivate you to study Chinese harder, just as looking at photos of delicious food might motivate you to improve your cooking skills.

You can also look into the limited range of wuxia available in English (or any other language you understand). Movies are most likely to be available in English.

For intermediate learners

For lower-intermediate learners, my advice is pretty much the same as for beginning learners, though one can be a little bolder – for example, checking out the Chinese version of one of the above websites, or trying to read/watch a bit of wuxia in Chinese.

At the upper-intermediate level, there are a lot more options. Some suggestions are:

- Read some comic books

- Try to watch a TV show

- Try one of the easier wuxia novels

I think it’s good to read comics and/or watch a TV show/movie before proceeding to novels, because a lot of things which happen in wuxia stories are much easier to understand visually than verbally, especially to people who are new to ideas such as 輕功.

I think that ‘reading a wuxia comic book’ and ‘reading an easier wuxia novel’ are roughly equivalent in difficulty. It of course depends on the comic book and the level being compared, but a comic book adapted from a Jin Yong novel is going to be at least as hard to read, if not harder, than a Gu Long novel.

Advanced learners

Go read a novel or watch a TV show or play a computer game.

But which one?

I think advanced learners main concern should not be the difficulty of the language, but how accessible the story itself is. Is the story fast-paced and suspenseful, or does it drag a lot at the beginning (i.e. is it The Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre/倚天屠龍記 where the main protagonist isn’t even mentioned once in the first 250 pages of the novel)? Does the story require familiarity with wuxia tropes, Chinese history, etc., or could my mother get it (if she suddenly knew Chinese)? Is it a good story?

These are concerns for intermediate learners too, of course.

And just like beginning learners, advanced learners should also have some background knowledge, especially before tackling the more difficult novels.

Movies/TV

I think this list offers a decent introduction to wuxia movies.

I have not seen too many wuxia TV shows, but one show I cannot recommend highly enough for advanced learners is State of Divinity (笑傲江湖) starring Jackie Lui (呂頌賢). People who have seen far more wuxia TV shows than I claim it’s one of the best ever made. I would go so far as to say, if you’re only going to watch one Chinese language TV drama of any genre in your entire lifetime, it should be this one.

This famous scene (YouTube) is great for studying the kind of language which appears often in wuxia stories, but it will make a lot more sense with a little context: Linghu Chong had been driven out of the Huashan sect. His greatest wish is to be accepted back by his sifu, Yue Buqun, leader of the Huashan sect, and to marry his daughter, Yue Lingshan, with whom he had developed the ‘Chong-Ling Sword Technique’. In the mean time, Ren Yingying had saved his life, so he feels he has to repay this debt of gratitude by freeing Ren Yingying and her father Ren Woxing from Shaolin Temple. Of course, many people object to releasing Ren Woxing because he is a megalomaniac. A deal has been struck that Ren Woxing and his daughter can go free if he wins two out of three duels. So far, he has won a duel and lost a duel…

This famous scene (YouTube) is great for studying the kind of language which appears often in wuxia stories, but it will make a lot more sense with a little context: Linghu Chong had been driven out of the Huashan sect. His greatest wish is to be accepted back by his sifu, Yue Buqun, leader of the Huashan sect, and to marry his daughter, Yue Lingshan, with whom he had developed the ‘Chong-Ling Sword Technique’. In the mean time, Ren Yingying had saved his life, so he feels he has to repay this debt of gratitude by freeing Ren Yingying and her father Ren Woxing from Shaolin Temple. Of course, many people object to releasing Ren Woxing because he is a megalomaniac. A deal has been struck that Ren Woxing and his daughter can go free if he wins two out of three duels. So far, he has won a duel and lost a duel…

This quote from episode 24 not only captures the essence of the TV show, but represents the mood of many, many, many wuxia stories.

當初我們四兄弟之所以加入日月神教,本想在江湖上可以行俠仗義,有所作為。哪知道任教主他性情暴戾,威福自用。當時我們四兄弟早萌退意,直到東方教主繼位更是寵信奸佞,誅除教中元老。我四人更是心灰意冷,決意隱居梅莊,並要看守要犯。一來,可以遠離黑木崖,不必與人勾心鬥角。二來,可以閒居西湖琴書遣懷。十二年來也可以說是享盡清福。不過人生在世,憂多樂少。人生本來就是如此了。

Automaticall generated version in simplified Chinese:当初我们四兄弟之所以加入日月神教,本想在江湖上可以行侠仗义,有所作为。哪知道任教主他性情暴戾,威福自用。当时我们四兄弟早萌退意,直到东方教主继位更是宠信奸佞,诛除教中元老。我四人更是心灰意冷,决意隐居梅莊,并要看守要犯。一来,可以远离黑木崖,不必与人勾心鬥角。二来,可以閒居西湖琴书遣怀。十二年来也可以说是享尽清福。不过人生在世,忧多乐少。人生本来就是如此了。

“When we four brothers first entered the Sun Moon Cult, we thought we could carry out heroic deeds all over jianghu. Who knew that Ren Woxing was so violent, and so hungry for power? Long after we four brothers had been disillusioned, Dongfang Bubai became the leader, and he loves wickedness even more. He executed all of the elders, and we four became even more disheartened. We decided to retreat to Plum Villa, and guard the prisoner. Firstly, far from Heimu Ya, we did not have to participate in all of the internecine struggle and backstabbing. Secondly, we could quietly live by Xihu, and fill our days with music and books. We can say that we have had twelve happy years. Nevertheless, in life the sorrows are many, and the joys are few. That is the nature of life.”

Wuxia novels

It’s hard to tell which novels are more or less suitable as an introduction to wuxia if you haven’t read them, and if you’ve read a bunch of wuxia novels, you are not a newcomer. That’s why, in my next article. I will introduce five wuxia novels which are good starting points for learners of Chinese who have never gotten into wuxia before. Stay tuned!

Continue reading the next article: A language learner’s guide to wuxia novels…

About Sara K

Sara K. has been studying Mandarin since Fall 2009. She grew up in San Francisco, California, and writes It Came From the Sinosphere for Manga Bookshelf, and has her own personal blog, The Notes Which Do Not Fit. She has previously written two articles on Hacking Chinese: A language learner’s guide to reading comics in Chinese and Approaches to reading in Chinese.

20 comments

WuXiaPedia !!!! I love it.

For some reason I have preferred Japanese comic books with Chinese language – in particular Doremon and Detective Conan.

Doremon has always attracted me for the amount of fantastic creativity that goes into all the silly gadgets he comes up with.

Conan is just a great ‘who-dun-it’ series with excellent art work.

When I do go to a comic book section in a book store, I am confronted by a huge wall of comic books with volumes running into the hundreds.

What I am primarily after is socially acceptible dialogue. The high frequency lexicon that I might use in everyday. Knowning about ‘little dragon girl’ can be useful, but the characters of pop culture can be hard to keep up with. I am not sure where this all may lead.

Geography is an important part of studying Chinese. For instance, China’s new aircraft carrier is named LiaoNing after a Chinese provence of great fame. Do some research to find out why.

Chinese medicine is a whole seperate lexicon. I started with that 30 years ago and have read quite a bit. But I wouldn’t say that it will get you very far in chit-chat over a dinner table. My favorite herb is Hwang Qi or Astragalus… much better tonic that the over-rated ginseng.

WuXia seems to get into a huge pop mythology of its own that I wasn’t aware of.

當初我們四兄弟之所以加入日月神教,本想在江湖上可以行俠仗義,有所作為。哪知道任教主他性情暴戾,威福自用。當時我們四兄弟早萌退意,直到東方教主繼位更是寵信奸佞,誅除教中元老。

Don’t forget the spcnet.tv forums, which have translations of tons of wuxia books.

http://www.spcnet.tv/forums/forumdisplay.php/29-Wuxia-Translations

Excellent article and decent advice. As Chinese, I recommend you watching Wuxia TV drama produced by Hongkong(aka, TVB, Television and Broadcasting Limited)rather than mainland China. Most mainland Chinese give heavy criticisms to mainland produced ones, complaining the lack of Wuxia spirit.

some additional comments.

The theme musics from Wuxia drama will be extremely helpful for you to understand the artistic conceptions, at least it works for native Chinese. Every Chinese hearing such genre of music would temporally forget reality and shift himself into the world of Wuxia.

As for ‘Xiaolongnü’, logically it’s clear that this person is not alive meaning she can’t exist in real world, yet you have to have a knowledge of Taosim philosophy to understand what this person really implies. This rule applies to almost every major character in Jinyong’s novel. Without the knowledge of Chinese philosophy of Confucianism and Taoism, especially Taoism, it will be impossible to understand what author really expresses in his words.

This is a great resource! Makes me want to start reading wuxia. 🙂

very interesting for sure wuxia influenced me to learn more and more Chinese language now am in HSK 2-3, hopefully with the help of you tube movies and TV wuxia series i can improve a lot, i must practice and live this third side of the coin is very interesting, taonism, confusianism

It’s also worth mentioning that people interested in something similar but with a bit more fantasy flavor to it might enjoy the 仙侠 Xianxia or 玄幻 Xuanhuan genres. Xianxia tends to focus on Daoist protagonists striving for immortality while fighting demons and the like, and Xuanhuan similarly features folklore and mythology elements but with a less strong focus on Daoist cultivation while sometimes mixing in foreign fantasy elements.

If you’re interested in getting into those genres I recommend looking up a site called Immortal Mountain on WordPress. They have articles explaining some of the core concepts as well as some small lists of relevant vocabulary that are more specific to those genres.

Watching a translated Xianxia series was actually what got me interested in learning Mandarin!

Thanks for sharing! Those are very good suggestions and I’m sure there are other learners who also find related genres interesting. I actually haven’t read that much myself, but feel that I ought too!

thanks for sharing, i am late reading this article.

what is your opinion about xianxia?, wuxia is declining now and been replaced by xianxia, i miss the old day when my online friends called each other sute, sumoi, suheng, suci (shi xiong, shi jie, shi di in Hokkien language).

Even the poem of Li Mochou is so popular and often repeated by people, “ask the world, what is love?…” :p