Learning is about connecting something new to what you already know. If what you know is clearly structured and logical, it’s much easier to fit new knowledge in your mental system, and you will find that remembering characters and words becomes much easier.

This is similar to learning anatomy: it’s easier to learn muscles of the human body if you have a good grasp of what the skeleton looks like first. Without that, knowledge about muscles is detached and meaningless. Structure matters.

A web with many layers

Knowledge of Chinese can be viewed as a web with several layers. At the highest level we have sentences, then words, characters and, finally, character components.

One problem for many learners is that they don’t spend enough energy connecting the various layers. They learn components, but don’t know how they work in different characters, or learn grammar words without knowing how they work in sentences.

The opposite is also true, of course, i.e. learning words without knowing the characters or learning sentences without having a clue about how they work. This is okay for beginners, because learning useful words and phrases as chunks is a great way of learning to communicate quickly, but the more advanced you become, the more you actually need to understand, not just mechanically repeat.

This is something I’ve thought a lot about recently, and I have arrived at a metaphor that includes three ways you can integrate knowledge. You can do this when learning something the first time or when you want to integrate something that feels detached and therefore hard to remember, such as a leech.

- Zooming in (this article) – Moving from a higher to a lower level: sentences to words to characters to components. Breaking things down in order to understand them.

- Zooming out – Moving from a lower to a higher level: components to characters to words to sentences. Putting things in context in order to understand them.

- Panning – Exploring the nearby areas of the web without either zooming in or out. Understand how similar things are different and how different things are similar.

This article is not meant to deal with the question of how much time you should spend on each level of the web, if you should focus mostly on sentences, phrases, words, characters or components. Obviously, you need all of them, but which one you should focus on the most depends on what you already know and what your goals are.

In short, though, the more practical and short-term your goal is, the higher up in the web you should focus. I’ve written more about the risk of not seeing the forest for the trees here: Focusing on radicals, character components and building blocks

Tools and resources for zooming in

Now, though, I want to give you the tools you need to zoom in. I will deal with zooming out and panning in upcoming articles. You might think that one good dictionary would take care of all this, but unfortunately, that’s not the case. Different dictionaries are good at different things.

Zooming in: Understanding composition and details

Zooming in means breaking things down to understand both the composition and the component parts. When it’s a sentence, it means words, when it’s a word, it means individual characters, and when it’s a character, it means character components.

Zooming is about how these fit together, so when it comes to sentences, it’s parts of speech and syntax; when it comes to words, it’s about the function of each character (看书/看書 “to read a book” is a verb-object composition, for instance); and for characters it’s about the components and their functions (in the character 洋 “ocean”, the meaning comes from 氵 “water” and the pronunciation from 羊 “sheep”, read more about semantic-phonetic compounds here).

Zooming in is the hardest of the three methods, because it not only requires reliable information about the words, characters and character components, it also requires understanding of how Chinese works. Just knowing what the components are isn’t always enough.

For instance, even though 救火 “to fight fire” and 救生 “save a life” are both verb-object constructions, it’s also obvious that they are different (you save a life, but you don’t save the fire). If you want to know more about this, you should read up on case grammar, but it’s not easy to find material in English about Chinese case grammar.

Similarly, when learning 洋, it’s not enough to just know that one part means “water” and the other “sheep”, you need to know which functions they have in that character. This is easier to figure out because you can make an educated guess based on the meaning and pronunciation of the components.

I can’t help you with all those things in this article, but I am going to give you the tools you need to find the information. Let’s start with sentences and then move down to words and characters.

Zooming in on sentences

This is very easy if you have the right tools, although correctly separating a sentence into its components words can be tricky as a beginner. With digital tools, however, it’s a piece of cake:

- MDBG – Just paste the text you want to zoom in on. MDBG will give you a list of the words in that text with more information about each part. This works well enough for most purposes.

- Digital reading in general – If you haven’t read this article by David Moser yet (The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading), you should. If you follow his advice and use pop-up dictionaries and/or document readers, parsing sentences will become much easier.

- Optical Character Reading – OCR features of mobile apps like Pleco and Hanping are very useful for digitising and dealing with printed Chinese you find difficult to break down and understand.

Zooming in on Words

- ABC Chinese-English Dictionary – Offers basic composition of words as mentioned above (i.e. it tells you that 救火 is a verb-object construction). Since this one is available as an add-on for both Pleco and Hanping, it’s easy to access on your mobile phone.

- Yellow Bridge (online) – Also offers information on word composition, this time online and for free, but with lots of ads.

Zooming in on characters

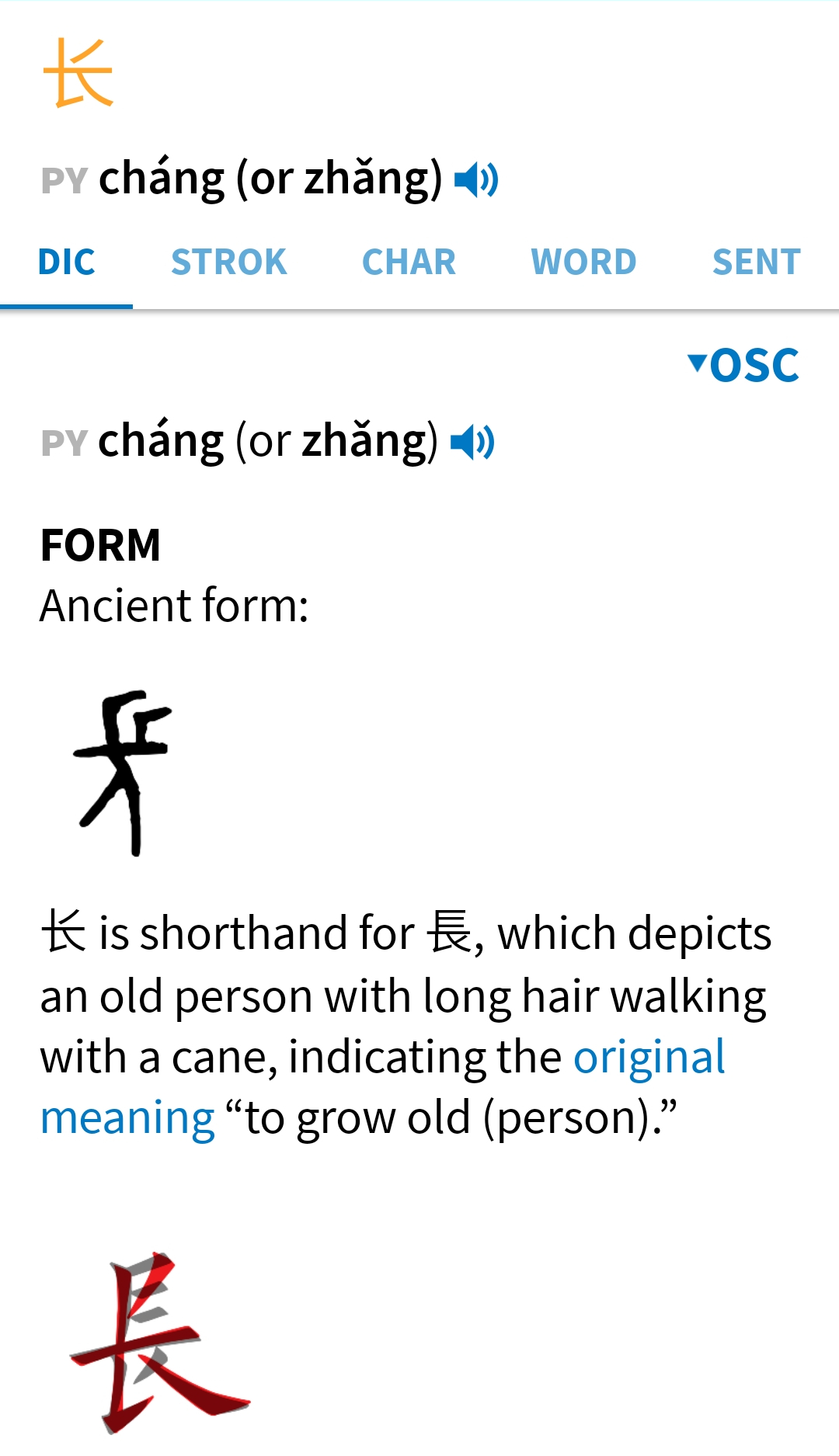

Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters – This is a (paid) add-on to Pleco that contains character breakdowns and information about character origin and evolution, curated by experts. It also makes a big point to tell you why a certain component is in the character. What function does it have? How does it contribute to the meaning and/or sound?

Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters – This is a (paid) add-on to Pleco that contains character breakdowns and information about character origin and evolution, curated by experts. It also makes a big point to tell you why a certain component is in the character. What function does it have? How does it contribute to the meaning and/or sound?- 漢典 (Zdic.net) – This is the best place to go online if you want information about individual characters. Among other things, it offers the type of character, as well as the functions of the components (in many cases, not all). This information is in Chinese, but it’s fairly easy to figure out. Check the included screen on the right where it says 字形分析. It first tells you it’s a left-right composition (左右结构), then that it’s a phonetic-semantic compound (形声), then where the sound comes from (羊声).

- HanziCraft – Although this is not a dictionary and not manually edited (and thus not very reliable), it does have the valuable function of giving you pronunciation clues, for instance: “Pronunciation clue for 洋 (yang2): The component 羊 is pronounced as ‘yang2’. It has the exact same pronunciation as the character.”

- Chinese Etymology – If you want more information about how the character has evolved, this is a good place to start. This isn’t always helpful for understanding the modern form without knowing more about characters, but it’s still useful.

Stay tuned

In the next article in this series, I will reverse the direction and zoom out, looking at tools and resources for adding context to make sense of what you’re learning and integrate it better into your web of knowledge. Continue reading:

Zooming out: The resources you need to put Chinese in context

2 comments

The link for MDBG is outdated: https://www.mdbg.net/chinese/dictionary

I have updated the link, thank you so much for pointing this out! 🙂